Babinet, Royer, and Jobert de Lamballe, all three members of the Institute, particularly distinguished themselves in this struggle between skepticism and supernaturalism, and most assuredly have reaped no laurels. The famous astronomer had imprudently risked himself on the battlefield of the phenomenon. He had explained scientifically the manifestations. But, emboldened by the fond belief among scientists that the new epidemic could not stand close investigation nor outlive the year, he had the still greater imprudence to publish two articles on them. As M. de Mirville very wittily remarks, if both of the articles had but a poor success in the scientific press, they had, on the other hand, none at all in the daily one.

M. Babinet began by accepting a priori, the rotation and movements of the furniture, which fact he declared to be “hors de doute.” “This rotation,” he said, “being able to manifest itself with a considerable energy, either by a very great speed, or by a strong resistance when it is desired that it should stop.”

Now comes the explanation of the eminent scientist. “Gently pushed by little concordant impulsions of the hands laid upon it, the table begins to oscillate from right to left. . . . At the moment when, after more or less delay, a nervous trepidation is established in the hands and the little individual impulsions of all the experimenters have become harmonized, the table is set in motion.”

He finds it very simple, for “all muscular movements are determined over bodies by levers of the third order, in which the fulcrum is very near to the point where the force acts. This, consequently, communicates a

Page 105

great speed to the mobile parts for the very little distance which the motor force has to run. . . . Some persons are astonished to see a table subjected to the action of several well-disposed individuals in a fair way to conquer powerful obstacles, even break its legs, when suddenly stopped; but that is very simple if we consider the power of the little concordant actions. . . . Once more, the physical explanation offers no difficulty.”

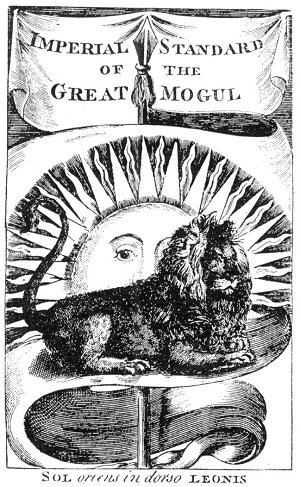

In this dissertation, two results are clearly shown: the reality of the phenomena proved, and the scientific explanation made ridiculous. But M. Babinet can well afford to be laughed at a little; he knows, as an astronomer, that dark spots are to be found even in the sun.

There is one thing, though, that Babinet has always stoutly denied, viz.: the levitation of furniture without contact. De Mirville catches him proclaiming that such levitation is impossible: “simply impossible,” he says, “as impossible as perpetual motion

Who can take upon himself, after such a declaration, to maintain that the word impossible pronounced by science is infallible?

But the tables, after having waltzed, oscillated and turned, began tipping and rapping. The raps were sometimes as powerful as pistol-detonations. What of this? Listen: “The witnesses and investigators are ventriloquists!”

De Mirville refers us to the Revue des Deux Mondes, in which is published a very interesting dialogue, invented by M. Babinet speaking of himself to himself, like the Chaldean En-Soph of the Kabalists: “What can we finally say of all these facts brought under our observation? Are there such raps produced? Yes. Do such raps answer questions? Yes. Who produces these sounds? The mediums. By what means? By the ordinary acoustic method of the ventriloquists. But we were given to suppose that these sounds might result from the cracking of the toes and fingers? No; for then they would always proceed from the same point, and such is not the fact.”

“Now,” asks de Mirville, “what are we to believe of the Americans, and their thousands of mediums who produce the same raps before millions of witnesses?” “Ventriloquism, to be sure,” answers Babinet. “But how can you explain such an impossibility?” The easiest thing in the world; listen only: “All that was necessary to produce the first manifestation in the first house in America was, a street-boy knocking at the door of a mystified citizen, perhaps with a leaden ball attached to a

Page 106

string, and if Mr. Weekman (the first believer in America) (?) when he watched for the third time, heard no shouts of laughter in the street, it is because of the essential difference which exists between a French street-Arab, and an English or Trans-Atlantic one, the latter being amply provided with what we call a sad merriment, “gaite triste.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.