During the course of my research into ancient tattoos, I had come across this fascinating book on Gnosticism written during the 18th century. The book is titled, The Gnostics and Their Remains, Ancient and Mediaeval by Charles William King and in it the author describes this mysterious tattooed man that adorns the artwork of the Book of Kells. He also relates these tattoos to a fascinating and believable connection between Ptolemy Philopator who had received Dionysiac brand-marks, St John, Masonic Brand marks and biblical prophecy.

During the course of my research into ancient tattoos, I had come across this fascinating book on Gnosticism written during the 18th century. The book is titled, The Gnostics and Their Remains, Ancient and Mediaeval by Charles William King and in it the author describes this mysterious tattooed man that adorns the artwork of the Book of Kells. He also relates these tattoos to a fascinating and believable connection between Ptolemy Philopator who had received Dionysiac brand-marks, St John, Masonic Brand marks and biblical prophecy.

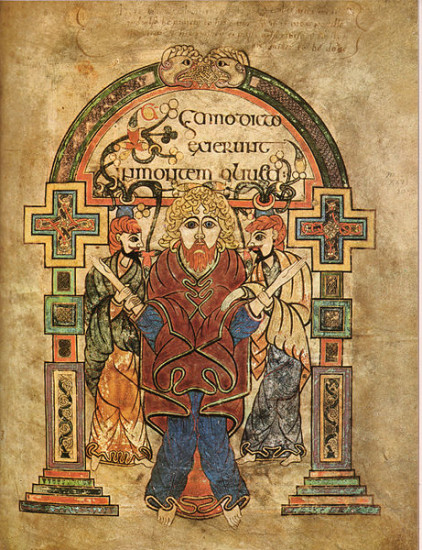

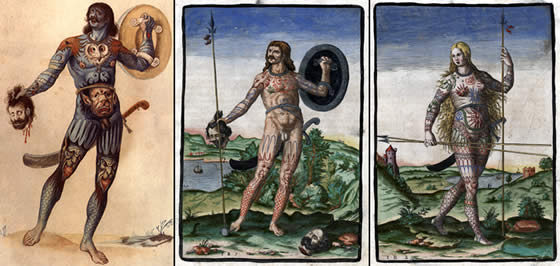

This reference to the Book of Kells I had confirmed in my own library by seeing this man that is obviously heavily tattooed in a blue ink. There is also another tattooed man with blond hair covered with red Celtic knot tattoos that is pictured to the left.

It is interesting to connect the tattoos left by these ancient brothers and sisters from Egypt, to Greece, and then to the West in countries such as Gaul, Ireland, Scotland and Denmark. These revelations are just more historical clues that add to the mounting apocalyptic physical evidence that has been left by these peoples for us historians.

Below is the excerpt that I’m writing about from the book, The Gnostics and Their Remains, Ancient and Mediaeval;

“The Book of Kells” is a MS., written some time in the ninth century. In one of the facsimiles of its pages published by the Palæographical Society, amongst the ornamentation of one vast initial letter, the most conspicuous is the figure of a naked man, writhing himself amongst its most intricate convolutions.

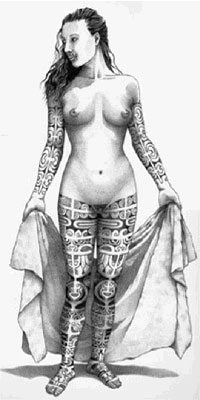

This man’s body is entirely covered with “marks” of various forms; and from the circumstances under which the drawing was made we can safely assume that we have here preserved to us the portrait of a true Pict, taken from the life.

The four centuries that had elapsed since Claudian wrote were not likely to have changed the customs of a country so remote, and in which the small amount of civilisation derivable from its Romanised neighbours must have gone backwards in proportion as they relapsed into their pristine barbarism. This pictured Pict may also lead us to conclude that the sigil seen upon the cheek of the Jersey Hercules was actually tattooed upon that of the Gaul who issued the coin.

Out of deference to the popular belief in the Masonic Brand mark, I shall wind up this section with a few observations upon that most time-honoured method of distinguishing those initiated into any mystic community. To give precedence to the Patron Saint of Freemasons, St. John the Divine, his making the followers of the Beast receive his Mark “upon the forehead and the palm of the hand,” is a clear allusion to the Mithraical practice, of which Augustine (as already quoted) speaks, in mentioning “a certain Demon, that will have his own image purchased with blood.”

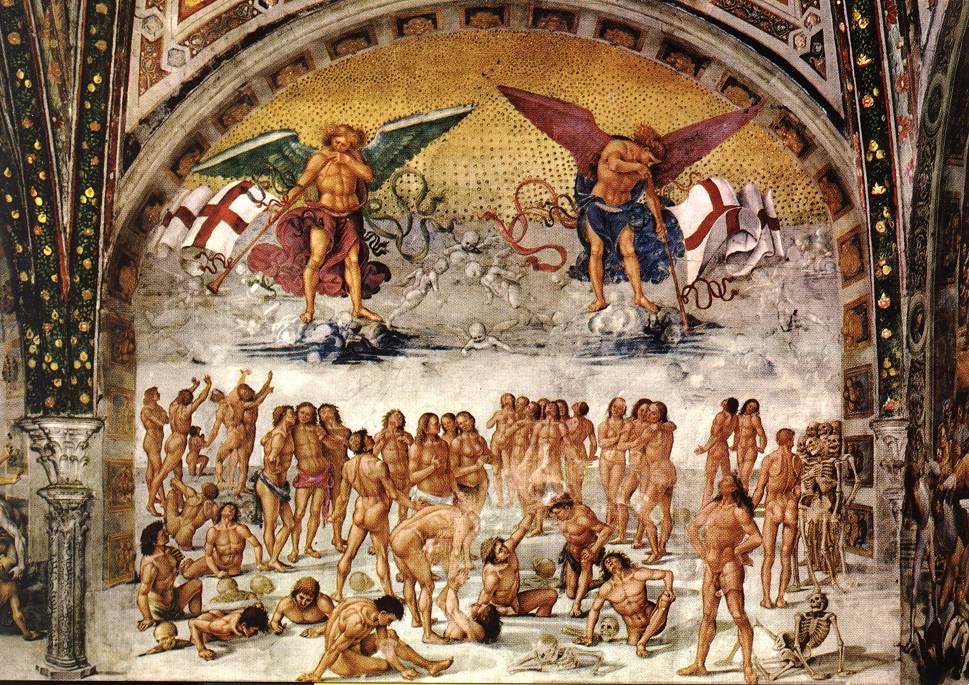

Ptolemy Philopator, whom Plutarch describes as “passing his sober hours in the celebration of Mysteries, and in beating a tambourine about the palace,” submitted also to receive the Dionysiac brand-marks; which were, no doubt, those symbols so plentifully introduced into the vase-paintings of Bacchanalian rites. “Brand-marks,” however, is an incorrect name for such insignia, for they were imprinted on the skin, not by fire, but by the milder process of Tattooing, as we learn incidentally from Vegetius (I. cap. 8), and also that it was the regular practice in the Roman army, in his day, the close of the fourth century. He advises that the recruit be not tattooed with the devices of the standards (Punctis signorum inscribendus est) until he has been proved by exercises as to whether he be strong enough for the service.

That these tattoo marks were the distinctive badges painted on the shields of the different legions, may be inferred from their insertion in the epitaphs of individuals of each corps.

Related articles

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.