Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel considered the intellectual intuition of von Schelling to be philosophically unsound and hence turned his attention to the establishment of a system of philosophy based upon pure logic. Of Hegel it has been said that he began with nothing and showed with logical precision how everything had proceeded from it in logical order. Hegel elevated logic to a position of supreme importance, in fact as a quality of the Absolute itself. God he conceived to be a process of unfolding which never attains to the condition of unfoldment. In like manner, thought is without either beginning or end. Hegel further believed that all things owe their existence to their opposites and that all opposites are actually identical. Thus the only existence is the relationship of opposites to each other, through whose combinations new elements are produced. As the Divine Mind is an eternal process of thought never accomplished, Hegel assails the very foundation of theism and his philosophy limits immortality to the everflowing Deity alone. Evolution is consequently the never-ending flow of Divine Consciousness out of itself; all creation, though continually moving, never arrives at any state other than that of ceaseless flow.

Johann Friedrich Herbart’s philosophy was a realistic reaction from the idealism of Fichte and von Schelling. To Herbart the true basis of philosophy was the great mass of phenomena continually moving through the human mind. Examination of phenomena, however, demonstrates that a great part of it is unreal, at least incapable of supplying the mind with actual truth. To correct the false impressions caused by phenomena and discover reality, Herbart believed it necessary to resolve phenomena into separate elements, for reality exists in the elements and not in the whole. He stated that objects can be classified by three general terms: thing, matter, and mind; the first a unit of several properties, the second an existing object, the third a self-conscious being. All three notions give rise, however, to certain contradictions, with whose solution Herbart is primarily concerned. For example, consider matter. Though capable of filling space, if reduced to its ultimate state it consists of incomprehensibly minute units of divine energy occupying no physical space whatsoever.

The true subject of Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophy is the will; the object of his philosophy is the elevation of the mind to the point where it is capable of controlling the will. Schopenhauer likens the will to a strong blind man who carries on his shoulders the intellect, which is a weak lame man possessing the power of sight. The will is the tireless cause of manifestation and every part of Nature the product of will. The brain is the product of the will to know; the hand the product of the will to grasp. The entire intellectual and emotional constitutions of man are subservient to the will and are largely concerned with the effort to justify the dictates of the will. Thus the mind creates elaborate systems of thought simply to prove the necessity of the thing willed. Genius, however, represents the state wherein the intellect has gained supremacy over the will and the life is ruled by reason and not by impulse. The strength of Christianity, said Schopenhauer, lay in its pessimism and conquest of individual will. His own religious viewpoints resembled closely the Buddhistic. To him Nirvana represented the subjugation of will. Life–the manifestation of the blind will to live–he viewed as a misfortune, claiming that the true philosopher was one who, recognizing the wisdom of death, resisted the inherent urge to reproduce his kind.

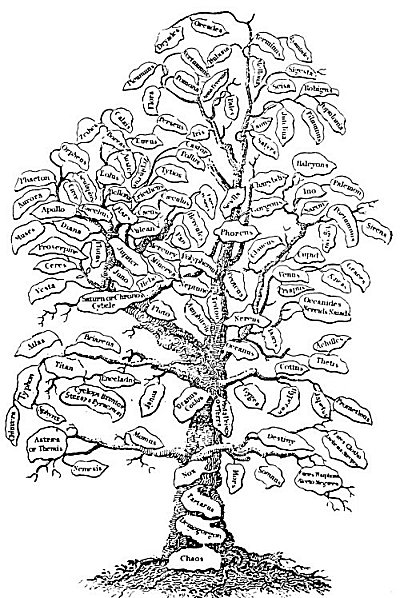

THE TREE OF CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY.

From Hort’s The New Pantheon. Before a proper appreciation of the deeper scientific aspects of Greek mythology is possible, it is necessary to organize the Greek pantheon and arrange its gods, goddesses, and various superhuman hierarchies in concatenated order. Proclus, the great Neo-Platonist, in his commentaries on the theology of Plato, gives an invaluable key to the sequence of the various deities in relation to the First Cause and the inferior powers emanating from themselves. When thus arranged, the divine hierarchies may be likened to the branches of a great tree. The roots of this tree are firmly imbedded in Unknowable Being. The trunk and larger branches of the tree symbolize the superior gods; the twigs and leaves, the innumerable existences dependent upon the first and unchanging Power.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.