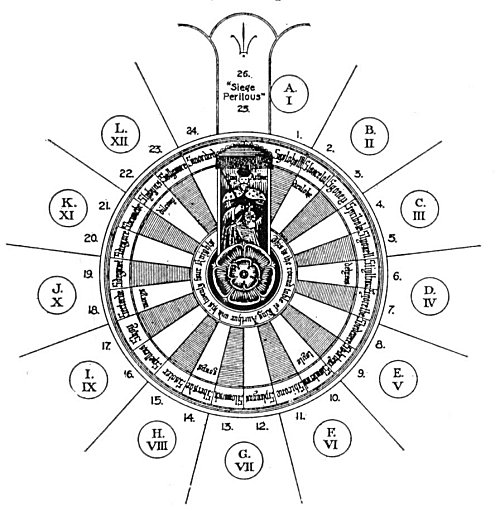

“Big Fish” is Cetus, the latinized form of Keto — [[Ketos]] and keto is Dagon, Poseidon, the female gender of it being Keton Atar-gatis — the Syrian goddess, and Venus, of Askalon. The figure or bust of Der-Keto or Astarte was generally represented on the prow of the ships. Jonah (the Greek Iona, or dove sacred to Venus) fled to Jaffa, where the god Dagon, the man-fish, was worshipped, and dared not go to Nineveh, where the dove was revered. Hence, some commentators believe that when Jonah was thrown overboard and was swallowed by a fish, we must understand that he was picked up by one of these vessels, on the prow of which was the figure of Keto. But the kabalists have another legend, to this effect: They say that Jonah was a run-away priest from the temple of the goddess where the dove was worshipped, and desired to abolish idolatry and institute monotheistic worship. That, caught near Jaffa, he was held prisoner by the devotees of Dagon in one of the prison-cells of the temple, and that it is the strange form of the cell which gave rise to the allegory. In the collection of Mose de Garcia, a Portuguese kabalist, there is a drawing representing the interior of the temple of Dagon. In the middle stands an immense idol, the upper portion of whose body is human, and the lower fish-like. Between the belly and the tail is an aperture which can be closed like the door of a closet. In it the transgressors against the local deity were shut up until further disposal. The drawing in question was made from an old tablet covered with curious drawings and inscriptions in old Phoenician characters, describing this Venetian

Page 259

oubliette of biblical days. The tablet itself was found in an excavation a few miles from Jaffa. Considering the extraordinary tendency of Oriental nations for puns and allegories, is it not barely possible that the “big fish” by which Jonah was swallowed was simply the cell within the belly of Dagon?

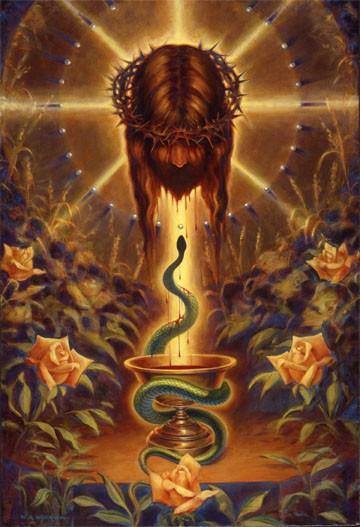

It is significant that this double appellation of “Messiah” and “Dag” (fish), of the Talmudists, should so well apply to the Hindu Vishnu, the “Preserving” Spirit, and the second personage of the Brahmanic trinity. This deity, having already manifested itself, is still regarded as the future Saviour of humanity, and is the selected Redeemer, who will appear at its tenth incarnation or avatar, like the Messiah of the Jews, to lead the blessed onward, and restore to them the primitive Vedas. At his first avatar, Vishnu is alleged to have appeared to humanity, in form like a fish. In the temple of Rama, there is a representation of this god which answers perfectly to that of Dagon, as given by Berosus. He has the body of a man issuing from the mouth of a fish, and holds in his hands the lost Veda. Vishnu, moreover, is the water-god, in one sense, the Logos of the Parabrahm, for as the three persons of the manifested god-head constantly interchange their attributes, we see him in the same temple represented as reclining on the seven-headed serpent, Ananta (eternity), and moving, like the Spirit of God, on the face of the primeval waters.

Vishnu is evidently the Adam Kadmon of the kabalists, for Adam is the Logos or the first Anointed, as Adam Second is the King Messiah.

Lakmy, or Lakshmi, the passive or feminine counterpart of Vishnu, the creator and the preserver, is also called Ada Maya. She is the “Mother of the World,” Damatri, the Venus Aphrodite of the Greeks: also Isis and Eve. While Venus is born from the sea-foam, Lakmy springs out from the water at the churning of the sea; when born, she is so beautiful that all the gods fall in love with her. The Jews, borrowing their types wherever they could get them, made their first woman after the pattern of Lakmy. It is curious that Viracocha, the Supreme Being in Peru, means, literally translated, “foam of the sea.”

Eugene Burnouf, the great authority of the French school, announces his opinion in the same spirit: “We must learn one day,” he observes, “that all ancient traditions disfigured by emigration and legend, belong to the history of India.” Such is the opinion of Colebrooke, Inman, King, Jacolliot, and many other Orientalists.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.