By Miguel Conner – One of the most important events in occult history was the 2009 publication of C.G. Jung’s Red Book. The full impact of this massive tome remains to be seen, although it probably has already been seen—since Jung claimed that all of his world-changing ideas were but a fraction of what was contained in this work. But by understanding how the Red Book came into being, we can also understand how the ancient heresy known as Gnosticism influenced our culture through the “Swiss Magician,” as Jung is known today.

seen—since Jung claimed that all of his world-changing ideas were but a fraction of what was contained in this work. But by understanding how the Red Book came into being, we can also understand how the ancient heresy known as Gnosticism influenced our culture through the “Swiss Magician,” as Jung is known today.

After all, the Red Book is, at its heart, a Gnostic Gospel because of its prevalent theme and ultimate thrust: the recovery of the soul from the darkness of mere being, and its awakened ascent through the astral spheres of reality until it is unified with the very font of all realities (and unrealities).

But it’s better to first and briefly understand the history of the Red Book (also known as the Liber Novus, or Latin for “New Book”). Jung began writing the Red Book sometime in 1914, shortly after falling out with his mentor, Sigmund Freud. The reasons for the split between the two fathers of psychology have to do with Freud rejecting Jung’s more spiritual approaches in understanding the human psyche. Perhaps because of the split, although it’s not entirely known, Jung soon after began having paranormal experiences and visions; these were often haunting and disturbing, affecting his family and residence. They were recorded for the next seven years, mostly in early drafts that would later become the Red Book.

Some have posited that Jung simply went insane through the period when he wrote the Red Book, and found through his psychic ordeal the means in which to recover his sanity. And then he used these insights to help his patients to recover their own sanity.

Jung hinted throughout his life at having the Red Book— which he wrote in personalized calligraphy and added elegant images—but he never revealed it to anyone. After his death in 1961, his family kept the work in a vault in Zurich, Switzerland, refusing any entreaties from his followers to bring it to the general public. Yet almost a century since it was written, Jung’s family yielded to pressure and the Red Book was eventually published (the process spearheaded by the Philemon Foundation).

The contents of the book are not so easy to detail, though. Beautiful and haunting, sophisticated yet often psychedelic, the Red Book is an evocative journey of Jung crossing dreamlike worlds. Some scenes are very disturbing, pregnant with cannibalism, atypical sex scenes, and landscapes that might come from an alien planet or religious underworld. In one scene, one of the many echoes of Gnostic wisdom, Jung carries a sick and decrepit God on his back.

English: Carl Gustav Jung, full-length portrait, standing in front of building in Burghölzi, Zurich (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The characters Jung encounters in these mythic realms are prominent figures from the Bible and other faiths, although their roles are just as unorthodox as the story itself (such as the biblical Elijah and Salome being married and acting as his spiritual advisors). Central to this magical account is a character named Philemon, who basically serves as Jung’s higher-self or Daemon (a concept prevalent in Gnosticism and esoteric Hellenistic thought). Jung’s own soul manifests throughout the book as a beautiful female (another ancient Gnostic trope) and indicates in one part that insanity is the only choice before reaching enlightenment, and further says, “If you want to find paths, you should also not spurn madness, since it makes up such a great part of your nature.”

The Red Book also contains gems of sound religious wisdom, such as one section where Jung writes, “God is where you are not.”

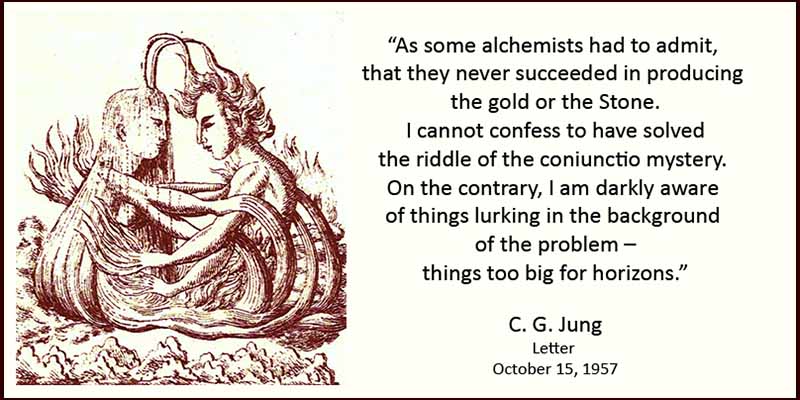

Every reader will have a different reaction and collect different insights from the shifting epic that is the Red Book. But the salient point is that Jung reconstructed the classic Gnostic technique of unlocking the Divine Spark by doing what he called “active imagination,” where an individual in essence invents, undergoes, and records an odyssey into transcendent realms (or the Collective Unconscious, as Jung would refer to it). In psychological terms, it is descending into the hidden domains of the personality, in order to heal trauma and recover fragmented emotions, ultimately to attain a state of wholeness or individuation. In Gnostic terms, it’s called having Gnosis. Jung simply perfected many of the ideas and exercises of the ancient Gnostic and Neoplatonists—suppressed by centuries of Orthodoxy—and then implemented to create what is known today as depth psychology.

Jung himself admitted that he was greatly influenced by the ancient Gnostics (even referring to them as his long, lost friends, as well as history’s first depth psychologists). While writing the Red Book, Jung also wrote the very surreal The Seven Sermons to the Dead, where he takes the role of the Gnostic sage Basilides, teaching the mysteries of the super-deity Abraxas.

It’s really no surprise that Gnosticism would have been a main force in many of Jung’s ideas, such as archetypes, personality types, spiritual alchemy, dream therapy, and the Collective Unconscious. Many scholars and theologians have proposed that the Gnostics were some of history’s most intense mystics and psychic deconstructionists. As scholar Erik Davies said in his book, Nomad Codes:

“And this way out (Gnosis) is way out—Gnostic texts crackle with a peculiar energy, an almost sci-fi sensibility of ‘alien gods’ and supramundane universes of light. Though not the first cosmic dualists, the Gnostics may have been the first spiritual off worlders.”

There is much more to the long history and release of the Red Book. But, like its future impression on civilization, are not as important as actually reading the work to find your own mystic revelations. And even more important—as Jung and the Gnostics advised in order to change outer and inner worlds—is the reality that each one of us must document our own journey to higher planes of existence, even if we have to enter the underworlds of our injured past. We all have already taken this journey, though. It’s simply a matter of remembering it and becoming as committed as Jung.

After all, Jung and the Gnostics ultimately wanted one simple thing for all of humanity: ultimate liberation.