“V. Should there exist any other secret means of guarding against the abuse of that authority entrusted by the order to our Superiors, what might they be?”

“VI. Supposing despotism were to ensure, would it be dangerous in the hands of men who, from the very first step we made in the Order, teach us nothing but science, liberty, and virtue? Would not that despotism lose its sting, in the consideration that those chiefs who may have conceived dangerous plans will have begun by disposing a machine in direct opposition to their views.” 2

To understand the tendency of these questions, let us reflect on the meaning given by the Sect to liberty and general welfare. Above all, let us not forget the lesson already given to the adepts on morality; the art of teaching men to shake off the yoke of their minority, to set aside Princes and Rulers, and to learn to govern themselves. This lesson once well understood, the most contracted understanding must perceive, in spite of the insidious tenour of these questions, that their sole tendency is to ask, whether “a Sect would be very dangerous who, under pretence of hindering the chiefs of nations, Kings, Ministers, and Magistrates, from hurting the people, should begin by mastering the opinions of all those who surrounded Kings, Ministers, or Magistrates; or should seek by invisible means to captivate all the councils, and the agents of

p. 497

public authority, in order to reinstate mankind in the rights of their pretended majority; and to teach the subject to throw off the authority of his Prince, and learn to govern himself; or, in other words, to destroy every King, Minister, Law, Magistrate, and public authority whatever?” The Candidate, too well-trained to the spirit of Illuminism not to see the real tendency of these questions, but also too much perverted by it to be startled at them, knows what answers he is to give to obtain the new degree. Should he still harbour doubts, the ceremonies of his installation would divest him of them. These are not theosophical or insignificant ceremonies;—every step demonstrates the disorganizing genius, and the hatred for all authority, which irritates the spleen of their impious author; and it is therefore that Weishaupt, when writing to Zwack, represents them as infinitely more important than those of the preceding degree. 3

When the admission of the new adept is resolved on, he is informed, “that as in future he is to be entrusted with papers belonging to the Order, of far greater importance than any that he has yet had in his possession, it is necessary that the Order should have further securities. He is therefore to make his will, and insert a particular clause with respect to any private papers which he may leave in case of sudden death. He is to get a formal and

juridical receipt of that part of his will from his family, or from the public Magistrate, and he is to take their promises in writing that they will fulfil his intentions.” 4

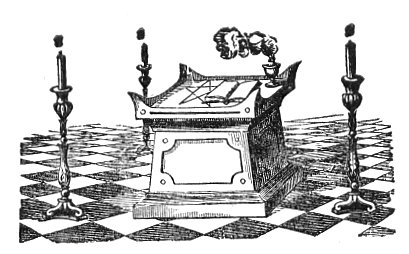

This precaution taken, and the day for the initiation fixed, the adept is admitted into an antichamber hung with black. Its furniture consists in a skeleton elevated on two steps, at the feet of which are laid a crown and a sword—There he is asked for the written dispositions he has made concerning the papers with which he may be entrusted, and the juridical promise he has received that his intentions shall be fulfilled. His hands are then loaded with chains, as if he were a slave; and he is thus left to his meditations. 5 The Provincial who performs the functions of Initiator is alone in the first saloon, seated on a throne. The Introducer, having left the Candidate to his reflections, enters this room, and in a voice loud enough to be heard by the new adept, the following Dialogue takes place between them.

“Provincial. Who brought this slave to us?”

“Introducer. He came of his own accord; he knocked at the door.”

“Prov. What does he want?”

“Introd. He is in search of Liberty, and asks to be freed from his chains.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.