Thomas Taylor has written, “Man is naturally a religious animal.” From the earliest dawning of his consciousness, man has worshiped and revered things as symbolic of the invisible, omnipresent, indescribable Thing, concerning which he could discover practically nothing. The pagan Mysteries opposed the Christians during the early centuries of their church, declaring that the new faith (Christianity) did not demand virtue and integrity as requisites for salvation. Celsus expressed himself on the subject in the following caustic terms:

“That I do not, however, accuse the Christians more bitterly than truth compels, may be conjectured from hence, that the cryers who call men to other mysteries proclaim as follows: ‘Let him approach whose hands are pure, and whose words are wise.’ And again, others proclaim: ‘Let him approach who is pure from all wickedness, whose soul is not conscious of any evil, and who leads a just and upright life.’ And these things are proclaimed by those who promise a purification from error. Let us now hear who those are that are called to the Christian mysteries: Whoever is a sinner, whoever is unwise, whoever is a fool, and whoever, in short, is miserable, him the kingdom of God will receive. Do you not, therefore, call a sinner, an unjust man, a thief, a housebreaker, a wizard, one who is sacrilegious, and a robber of sepulchres? What other persons would the cryer nominate, who should call robbers together?”

It was not the true faith of the early Christian mystics that Celsus attacked, but the false forms that were creeping in even during his day. The ideals of early Christianity were based upon the high moral standards of the pagan Mysteries, and the first Christians who met under the city of Rome used as their places of worship the subterranean temples of Mithras, from whose cult has been borrowed much of the sacerdotalism of the modem church.

The ancient philosophers believed that no man could live intelligently who did not have a fundamental knowledge of Nature and her laws. Before man can obey, he must understand, and the Mysteries were devoted to instructing man concerning the operation of divine law in the terrestrial sphere. Few of the early cults actually worshiped anthropomorphic deities, although their symbolism might lead one to believe they did. They were moralistic rather than religionistic; philosophic rather than theologic. They taught man to use his faculties more intelligently, to be patient in the face of adversity, to be courageous when confronted by danger, to be true in the midst of temptation, and, most of all, to view a worthy life as the most acceptable sacrifice to God, and his body as an altar sacred to the Deity.

Sun worship played an important part in nearly all the early pagan Mysteries. This indicates the probability of their Atlantean origin, for the people of Atlantis were sun worshipers. The Solar Deity was usually personified as a beautiful youth, with long golden hair to symbolize the rays of the sun. This golden Sun God was slain by wicked ruffians, who personified the evil principle of the universe. By means of certain rituals and ceremonies, symbolic of purification and regeneration, this wonderful God of Good was brought back to life and became the Savior of His people. The secret processes whereby He was resurrected symbolized those cultures by means of which man is able to overcome his lower nature, master his appetites, and give expression to the higher side of himself. The Mysteries were organized for the purpose of assisting the struggling human creature to reawaken the spiritual powers which, surrounded by the flaming

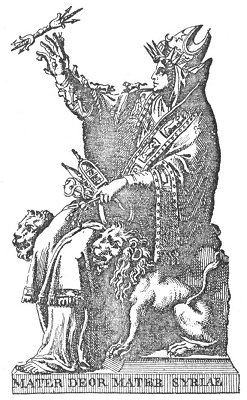

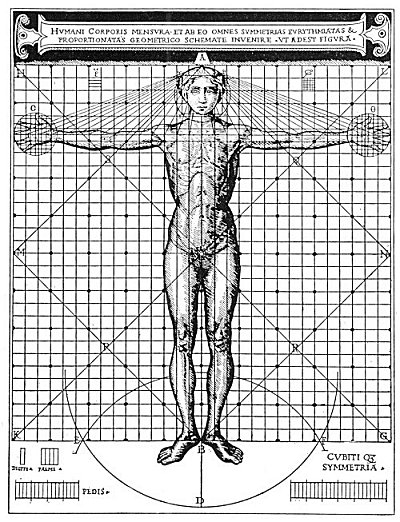

A FEMALE HIEROPHANT OF THE MYSTERIES.

From Montfaucon’s Antiquities. This illustration shows Cybele, here called the Syrian Goddess, in the robes of a hierophant. Montfaucon describes the figure as follows: “Upon her head is an episcopal mitre, adorned on the lower part with towers and pinnacles; over the gate of the city is a crescent, and beneath the circuit of the walls a crown of rays. The Goddess wears a sort of surplice, exactly like the surplice of a priest or bishop; and upon the surplice a tunic, which falls down to the legs; and over all an episcopal cope, with the twelve signs of the Zodiac wrought on the borders. The figure hath a lion on each side, and holds in its left hand a Tympanum, a Sistrum, a Distaff, a Caduceus, and another instrument. In her right hand she holds with her middle finger a thunderbolt, and upon the same am animals, insects, and, as far as we may guess, flowers, fruit, a bow, a quiver, a torch, and a scythe.” The whereabouts of the statue is unknown, the copy reproduced by Montfaucon being from drawings by Pirro Ligorio.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.