by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 325

THE true Mason is a practical Philosopher, who, under religious emblems, in all ages adopted by wisdom, builds upon plans traced by nature and reason the moral edifice of knowledge. He ought to find, in the symmetrical relation of all the parts of this rational edifice, the principle and rule of all his duties, the source of all his pleasures. He improves his moral nature, becomes a better man, and finds in the reunion of virtuous men, assembled with pure views, the means of multiplying his acts of beneficence. Masonry and Philosophy, without being one and the same thing, have the same object, and propose to themselves the same end, the worship of the Grand Architect of the Universe, acquaintance and familiarity with the wonders of nature, and the happiness of humanity attained by the constant practice of all the virtues.

As Grand Master of all Symbolic Lodges, it is your especial duty to aid in restoring Masonry to its primitive purity. You have become an instructor. Masonry long wandered in error. Instead of improving, it degenerated from its primitive simplicity, and retrograded toward a system, distorted by stupidity and ignorance, which, unable to construct a beautiful machine, made a complicated one. Less than two hundred years ago, its organization was simple, and altogether moral, its emblems, allegories, and ceremonies easy to be understood, and their purpose and object readily to be seen. It was then confined to a very small number of Degrees. Its constitutions were like those of a Society of Essenes, written in the first century of our era. There could be seen the primitive Christianity, organized into Masonry, the school of Pythagoras without incongruities or absurdities; a Masonry simple and significant, in which it was not necessary to torture the mind to discover reasonable interpretations; a Masonry at once religious and philosophical, worthy of a good citizen and an enlightened philanthropist.

Innovators and inventors overturned that primitive simplicity.

p. 326

[paragraph continues] Ignorance engaged in the work of making Degrees, and trifles and gewgaws and pretended mysteries, absurd or hideous, usurped the place of Masonic Truth. The picture of a horrid vengeance, the poniard and the bloody head, appeared in the peaceful Temple of Masonry, without sufficient explanation of their symbolic meaning: Oaths out of all proportion with their object, shocked the candidate, and then became ridiculous, and were wholly disregarded. Acolytes were exposed to tests, and compelled to perform acts, which, if real, would have been abominable; but being mere chimeras, were preposterous, and excited contempt and laughter only. Eight hundred Degrees of one kind and another were invented: Infidelity and even Jesuitry were taught under the mask of Masonry. The rituals even of the respectable Degrees, copied and mutilated by ignorant men, became nonsensical and trivial; and the words so corrupted that it has hitherto been found impossible to recover many of them at all. Candidates were made to degrade themselves, and to submit to insults not tolerable to a man of spirit and honor.

Hence it was that, practically, the largest portion of the Degrees claimed by the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, and before it by the Rite of Perfection, fell into disuse, were merely communicated, and their rituals became jejune and insignificant. These Rites resembled those old palaces and baronial castles, the different parts of which, built at different periods remote from one another, upon plans and according to tastes that greatly varied, formed a discordant and incongruous whole. Judaism and chivalry, superstition and philosophy, philanthropy and insane hatred and longing for vengeance, a pure morality and unjust and illegal revenge, were found strangely mated and standing hand in hand within the Temples of Peace and Concord; and the whole system was one grotesque commingling of incongruous things, of contrasts and contradictions, of shocking and fantastic extravagances, of parts repugnant to good taste, and fine conceptions overlaid and disfigured by absurdities engendered by ignorance, fanaticism, and a senseless mysticism.

An empty and sterile pomp, impossible indeed to be carried out, and to which no meaning whatever was attached, with far-fetched explanations that were either so many stupid platitudes or themselves needed an interpreter; lofty titles, arbitrarily assumed, and to which the inventors had not condescended to attach any explanation

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 237

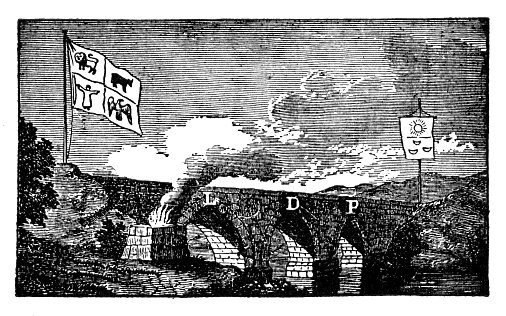

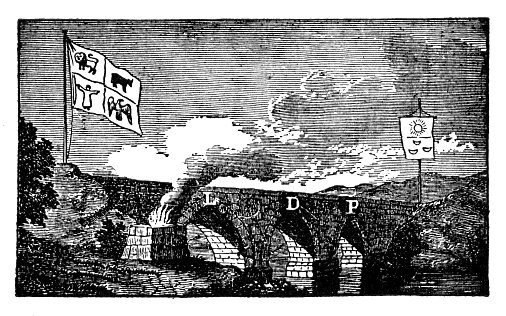

[Knight of the East, of the Sword, or of the Eagle.]

THIS Degree, like all others in Masonry, is symbolical. Based upon historical truth and authentic tradition, it is still an allegory. The leading lesson of this Degree is Fidelity to obligation, and Constancy and Perseverance under difficulties and discouragement.

Masonry is engaged in her crusade, against ignorance, intolerance, fanaticism, superstition, uncharitableness, and error. She does not sail with the trade-winds, upon a smooth sea, with a steady free breeze, fair for a welcoming harbor; but meets and must overcome many opposing currents, baffling winds, and dead calms.

The chief obstacles to her success are the apathy and faithlessness of her own selfish children, and the supine indifference of the world. In the roar and crush and hurry of life and business, and the tumult and uproar of politics, the quiet voice of Masonry is unheard and unheeded. The first lesson which one learns, who engages in any great work of reform or beneficence, is, that men are essentially careless, lukewarm, and indifferent as to everything that does not concern their own personal and immediate

p. 238

welfare. It is to single men, and not to the united efforts of many, that all the great works of man, struggling toward perfection, are owing. The enthusiast, who imagines that he can inspire with his own enthusiasm the multitude that eddies around him, or even the few who have associated themselves with him as co-workers, is grievously mistaken; and most often the conviction of his own mistake is followed by discouragement and disgust. To do all, to pay all, and to suffer all, and then, when despite all obstacles and hindrances, success is accomplished, and a great work done, to see those who opposed or looked coldly on it, claim and reap all the praise and reward, is the common and almost universal lot of the benefactor of his kind.

He who endeavors to serve, to benefit, and improve the world, is like a swimmer, who struggles against a rapid current, in a river lashed into angry waves by the winds. Often they roar over his head, often they beat him back and baffle him. Most men yield to the stress of the current, and float with it to the shore, or are swept over the rapids; and only here and there the stout, strong heart and vigorous arms struggle on toward ultimate success.

It is the motionless and stationary that most frets and impedes the current of progress; the solid rock or stupid dead tree, rested firmly on the bottom; and around which the river whirls and eddies: the Masons that doubt and hesitate and are discouraged; that disbelieve in the capability of man to improve; that are not disposed to toil and labor for the interest and well-being of general humanity; that expect others to do all, even of that which they do not oppose or ridicule; while they sit, applauding and doing nothing, or perhaps prognosticating failure.

There were many such at the rebuilding of the Temple. There were prophets of evil and misfortune–the lukewarm and the in-different and the apathetic; those who stood by and sneered; and those who thought they did God service enough if they now and then faintly applauded. There were ravens croaking ill omen, and murmurers who preached the folly and futility of the attempt. The world is made up of such; and they were as abundant then as they are now.

But gloomy and discouraging as was the prospect, with lukewarmness within and bitter opposition without, our ancient brethren persevered. Let us leave them engaged in the good work, and whenever to us, as to them, success is uncertain, remote, and

p. 239

contingent, let us still remember that the only question for us to ask, as true men and Masons, is, what does duty require; and not what will be the result and our reward if we do our duty. Work on, with the Sword in one hand, and the Trowel in the other!

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 160

[Elu of the Fifteen.]

THIS Degree is devoted to the same objects as those of the Elu of Nine; and also to the cause of Toleration and Liberality against Fanaticism and Persecution, political and religious; and to that of Education, Instruction, and Enlightenment against Error, Barbarism, and Ignorance. To these objects you have irrevocably and forever devoted your hand, your heart, and your intellect; and whenever in your presence a Chapter of this Degree is opened, you will be most solemnly reminded of your vows here taken at the altar.

Toleration, holding that every other man has the same right to his opinion and faith that we have to ours; and liberality, holding that as no human being can with certainty say, in the clash and conflict of hostile faiths and creeds, what is truth, or that he is surely in possession of it, so every one should feel that it is quite possible that another equally honest and sincere with himself, and yet holding the contrary opinion, may himself be in possession of the truth, and that whatever one firmly and conscientiously believes, is truth, to him–these are the mortal enemies of that fanaticism which persecutes for opinion’s sake, and initiates crusades against whatever it, in its imaginary holiness, deems to be contrary to the law of God or verity of dogma. And education, instruction, and enlightenment are the most certain means by which fanaticism and intolerance can be rendered powerless.

No true Mason scoffs at honest convictions and an ardent zeal in the cause of what one believes to be truth and justice. But he

p. 161

does absolutely deny the right of any man to assume the prerogative of Deity, and condemn another’s faith and opinions as deserving to be punished because heretical. Nor does he approve the course of those who endanger the peace and quiet of great nations, and the best interest of their own race by indulging in a chimerical and visionary philanthropy–a luxury which chiefly consists in drawing their robes around them to avoid contact with their fellows, and proclaiming themselves holier than they.

For he knows that such follies are often more calamitous than the ambition of kings; and that intolerance and bigotry have been infinitely greater curses to mankind than ignorance and error. Better any error than persecution! Better any opinion than the thumb-screw, the rack, and the stake! And he knows also how unspeakably absurd it is, for a creature to whom himself and everything around him are mysteries, to torture and slay others, because they cannot think as he does in regard to the profoundest of those mysteries, to understand which is utterly beyond the comprehension of either the persecutor or the persecuted.

Masonry is not a religion. He who makes of it a religious belief, falsifies and denaturalizes it. The Brahmin, the Jew, the Mahometan, the Catholic, the Protestant, each professing his peculiar religion, sanctioned by the laws, by time, and by climate, must needs retain it, and cannot have two religions; for the social and sacred laws adapted to the usages, manners, and prejudices of particular countries, are the work of men.

But Masonry teaches, and has preserved in their purity, the cardinal tenets of the old primitive faith, which underlie and are the foundation of all religions. All that ever existed have had a basis of truth; and all have overlaid that truth with errors. The primitive truths taught by the Redeemer were sooner corrupted, and intermingled and alloyed with fictions than when taught to the first of our race. Masonry is the universal morality which is suitable to the inhabitants of every clime, to the man of every creed. It has taught no doctrines, except those truths that tend directly to the well-being of man; and those who have attempted to direct it toward useless vengeance, political ends, and Jesuitism, have merely perverted it to purposes foreign to its pure spirit and real nature.

Mankind outgrows the sacrifices and the mythologies of the childhood of the world. Yet it is easy for human indolence to

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 119

[Confidential Secretary.]

You are especially taught in this Degree to be zealous and faithful; to be disinterested and benevolent; and to act the peace-maker, in case of dissensions, disputes, and quarrels among the brethren.

Duty is the moral magnetism which controls and guides the true Mason’s course over the tumultuous seas of life. Whether the stars of honor, reputation, and reward do or do not shine, in the light of day or in the darkness of the night of trouble and adversity, in calm or storm, that unerring magnet still shows him the true course to steer, and indicates with certainty where-away lies the port which not to reach involves shipwreck and dishonor. He follows its silent bidding, as the mariner, when land is for many days not in sight, and the ocean without path or landmark spreads out all around him, follows the bidding of the needle, never doubting that it points truly to the north. To perform that duty, whether the performance be rewarded or unrewarded, is his sole care. And it doth not matter, though of this performance there may be no witnesses, and though what he does will be forever unknown to all mankind.

A little consideration will teach us that Fame has other limits than mountains and oceans; and that he who places happiness in the frequent repetition of his name, may spend his life in propagating it, without any danger of weeping for new worlds, or necessity of passing the Atlantic sea.

If, therefore, he who imagines the world to be filled with his actions

p. 120

and praises, shall subduct from the number of his encomiasts all those who are placed below the flight of fame, and who hear in the valley of life no voice but that of necessity; all those who imagine themselves too important to regard him, and consider the mention of his name as a usurpation of their time; all who are too much or too little pleased with themselves to attend to anything external; all who are attracted by pleasure, or chained down by pain to unvaried ideas; all who are withheld from attending his triumph by different pursuits; and all who slumber in universal negligence; he will find his renown straitened by nearer bounds than the rocks of Caucasus; and perceive that no man can be venerable or formidable, but to a small part of his fellow-creatures. And therefore, that we may not languish in our endeavors after excellence, it is necessary that, as Africanus counsels his descendants, we raise our eyes to higher prospects, and contemplate our future and eternal state, without giving up our hearts to the praise of crowds, or fixing our hopes on such rewards as human power can bestow.

We are not born for ourselves alone; and our country claims her share, and our friends their share of us. As all that the earth produces is created for the use of man, so men are created for the sake of men, that they may mutually do good to one another. In this we ought to take nature for our guide, and throw into the public stock the offices of general utility, by a reciprocation of duties; sometimes by receiving, sometimes by giving, and sometimes to cement human society by arts, by industry, and by our resources.

Suffer others to be praised in thy presence, and entertain their good and glory with delight; but at no hand disparage them, or lessen the report, or make an objection; and think not the advancement of thy brother is a lessening of thy worth. Upbraid no man’s weakness to him to discomfit him, neither report it to disparage him, neither delight to remember it to lessen him, or to set thyself above him; nor ever praise thyself or dispraise any man else, unless some sufficient worthy end do hallow it.

Remember that we usually disparage others upon slight grounds and little instances; and if a man be highly commended, we think him sufficiently lessened, if we can but charge one sin of folly or inferiority in his account. We should either be more severe to ourselves, or less so to others, and consider that whatsoever good any one can think or say of us, we can tell him of many unworthy and

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 114

THE Master Khu_ru_m was an industrious and an honest man. What he was employed to do he did diligently, and he did it well and faithfully. He received no wages that were not his due. Industry and honesty are the virtues peculiarly inculcated in this Degree. They are common and homely virtues; but not for that beneath our notice. As the bees do not love or respect the drones, so Masonry neither loves nor respects the idle and those who live by their wits; and least of all those parasitic acari that live upon themselves. For those who are indolent are likely to become dissipated and vicious; and perfect honesty, which ought to be the common qualification of all, is more rare than diamonds. To do earnestly and steadily, and to do faithfully and honestly that which we have to do–perhaps this wants but little, when looked at from every point of view, of including the whole body of the moral law; and even in their commonest and homeliest application, these virtues belong to the character of a Perfect Master.

Idleness is the burial of a living man. For an idle person is so useless to any purposes of God and man, that he is like one who is dead, unconcerned in the changes and necessities of the world; and he only lives to spend his time, and eat the fruits of the earth. Like a vermin or a wolf, when his time comes, he dies and perishes, and in the meantime is nought. He neither ploughs nor carries burdens: all that he does is either unprofitable or mischievous.

It is a vast work that any man may do, if he never be idle: and it is a huge way that a man may go in virtue, if he never go out of his way by a vicious habit or a great crime: and he who perpetually

p. 115

reads good books, if his parts be answerable, will have a huge stock of knowledge.

St. Ambrose, and from his example, St. Augustine, divided every day into these tertias of employment: eight hours they spent in the necessities of nature and recreation: eight hours in charity, in doing assistance to others, dispatching their business, reconciling their enmities, reproving their vices, correcting their errors, instructing their ignorance, and in transacting the affairs of their dioceses; and the other eight hours they spent in study and prayer.

We think, at the age of twenty, that life is much too long for that which we have to learn and do; and that there is an almost fabulous distance between our age and that of our grandfather. But when, at the age of sixty, if we are fortunate enough to reach it, or unfortunate enough, as the case may be, and according as we have profitably invested or wasted our time, we halt, and look back along the way we have come, and cast up and endeavor to balance our accounts with time and opportunity, we find that we have made life much too short, and thrown away a huge portion of our time. Then we, in our mind, deduct from the sum total of our years the hours that we have needlessly passed in sleep; the working-hours each day, during which the surface of the mind’s sluggish pool has not been stirred or ruffled by a single thought; the days that we have gladly got rid of, to attain some real or fancied object that lay beyond, in the way between us and which stood irksomely the intervening days; the hours worse than wasted in follies and dissipation, or misspent in useless and unprofitable studies; and we acknowledge, with a sigh, that we could have learned and done, in half a score of years well spent, more than we have done in all our forty years of manhood.

To learn and to do!–this is the soul’s work here below. The soul grows as truly as an oak grows. As the tree takes the carbon of the air, the dew, the rain, and the light, and the food that the earth supplies to its roots, and by its mysterious chemistry trans-mutes them into sap and fibre, into wood and leaf, and flower and fruit, and color and perfume, so the soul imbibes knowledge and by a divine alchemy changes what it learns into its own substance, and grows from within outwardly with an inherent force and power like those that lie hidden in the grain of wheat.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.