by Moe | Aug 16, 2012 | Did You Know?, Featured

There are many people out there that are confused to the differences between the Left Hand Path (LHP) and Right Hand Paths (RHP). The facts are it is really simple to understand once you get educated. My hopes are that this article does this for you.

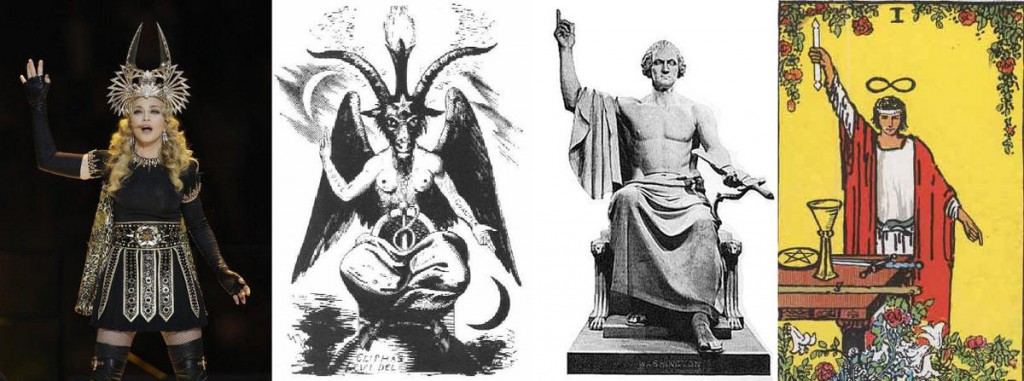

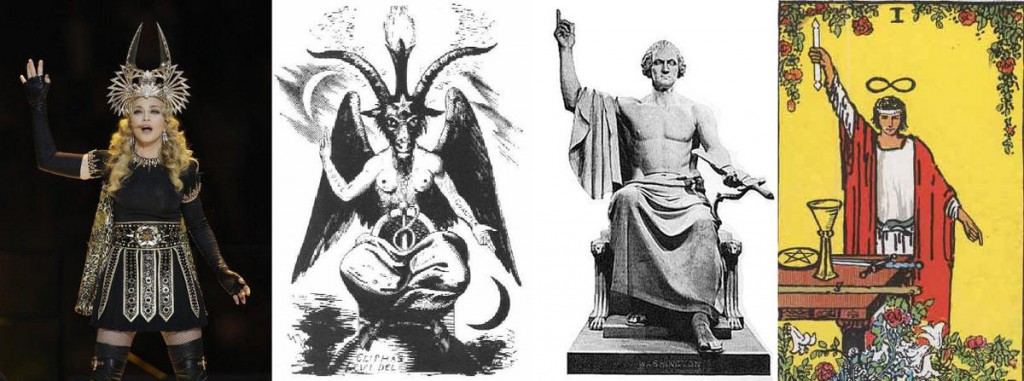

Please look at this pictures below where we have Madonna, Baphomet, our first President, George Washington and a Tarot Card all indicating AS ABOVE, SO BELOW. But also their hands signify the two different paths as well.

As you can see from the pictures above, you have the right hand pointing up and the left hand point down. The right hand is pointing to the light which is the right hand path to represent illumination and a higher consciousness. When you take this path, you choose the light. You are AS ABOVE, SO BELOW. (more…)

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Sep 3, 2011 | Code of the Illuminati

p. 486

In that part of the discourse which remains to be laid before the reader, the Hierophant, insisting on the necessity of enlightening the people to operate the grand revolution, seems to fear that the Candidate has not clearly conceived the real plan of this revolution, which is in future to be the sole object of all his instructions. “Let your instructions and lights be universally diffused; so shall you render mutual security universal; and security and instruction will enable us to live without prince or government. If that were not the case, why should we go in quest of either?” 1

Here then the Candidate is clearly informed of the grand object towards which he is to direct all his future instructions. To teach the people to live without princes or governments, without laws or even civil society, is to be the general tendency of all his lessons. But of what nature must these lessons be to attain the desired object?—They are to treat of morality, and of morality alone. “For (continues the Hierophant) if light be the work of morality, light and security will gain strength as morality expands itself. Nor is true morality any other than the art of teaching men to shake off their wardship, to attain the age of manhood, and thus to need neither princes nor governments.” 2

When we shall see the Sect enthusiastically pronouncing the word morality, let us recollect the definition which it has just given us of it. Without it, we could not have understood the real sense of the terms honest men, virtue, good or wicked men. We see that, according to this definition, the honest man is he who labours at the overthrow of civil society, its laws, and its chiefs: for these are the only crimes or virtues mentioned in the whole Code. Presupposing that the Candidate may object that it would be impossible to bring mankind to adopt such doctrines, the Hierophant anticipates the objection, and exclaims, “He is little acquainted with the powers of reason and the attractions of virtue; he is a very novice in the regions of light, who shall harbour such mean ideas as to his own essence, or the nature of mankind. . . .If either he or I can attain this point, why should not another attain it also? What! when men can be led to despise the horrors of death, when they may be inflamed with the enthusiasm of religious and political follies, shall they be deaf to that very doctrine which can alone lead them to happiness? No, no; man is not so wicked

p. 487

as an arbitrary morality would make him appear. He is wicked, because Religion, the State, and bad example, perverts him. It would be of advantage to those who wish to make him better, were there fewer persons whose interest it is to render him wicked in order that they may support their power by his wickedness.”

“Let us form a more liberal opinion of human nature. We will labour indefatigably, nor shall difficulties affright us. May our principles become the foundation of all morals! Let reason at length be the religion of men, and the problem is solved.” 3

This pressing exhortation will enable the reader to solve the problem of the altars, the worship, and the festivals of Reason, in the French Revolution; nor will they be any longer at a loss to know from what loathsome den their shameless Goddess rose.

The Candidate also obtains the solution of all that may have appeared to him problematic in the course of his former trials. “Since such is the force of morality and of morality alone (says the Hierophant), since it alone can operate the grand revolution which is to restore liberty to mankind, and abolish the empire of imposture, superstition, and despotism; you must now perceive why on their first entrance into our Order we oblige our pupils to apply closely to the study of morality, to the knowledge of themselves and of others. You must see plainly, that if we permit each Novice to introduce his friend, it is in order to form a legion that may more justly he called holy and invincible than that of the Theban; since the battles of the friend fighting by the side of his friend are those which are to reinstate human nature in its rights, its liberty, and its primitive independence.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Sep 2, 2011 | Ecclesiastical History of England

Some few years before their arrival, the Pelagian heresy, brought over by Agricola, the son of Severianus, a Pelagian bishop, had corrupted with its foul taint the faith of the Britons. But whereas they absolutely refused to embrace that perverse doctrine, and blaspheme the grace of Christ, yet were not able of themselves to confute the subtilty of the unholy belief by force of argument, they bethought them of wholesome counsels and determined to crave aid of the Gallican prelates in that spiritual warfare. Hereupon, these, having assembled a great synod, consulted together to determine what persons should be sent thither to sustain the faith, and by unanimous consent, choice was made of the apostolic prelates, Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, and Lupus of Troyes, to go into Britain to confirm the people’s faith in the grace of God. With ready zeal they complied with the request and commands of the Holy Church, and put to sea. The ship sped safely with favouring winds till they were halfway between the coast of Gaul and Britain. There on a sudden they were obstructed by the malevolence of demons, who were jealous that men of such eminence and piety should be sent to bring back the people to salvation. They raised storms, and darkened the sky with clouds. The sails could not support the fury of the winds, the sailors’ skill was forced to give way, the ship was sustained by prayer, not by strength, and as it happened, their spiritual leader and bishop, being spent with weariness, had fallen asleep. Then, as if because resistance flagged, the tempest gathered strength, and the ship, overwhelmed by the waves, was ready to sink. Then the blessed Lupus and all the rest, greatly troubled, awakened their elder, that he might oppose the raging elements. He, showing himself the more resolute in proportion to the greatness of the danger, called upon Christ, and having, in the name of the Holy Trinity, taken and sprinkled a little water, quelled the raging waves, admonished his companion, encouraged all, and all with one consent uplifted their voices in prayer. Divine help was granted, the enemies were put to flight, a cloudless calm ensued, the winds veering about set themselves again to forward their voyage, the sea was soon traversed, and they reached the quiet of the wished-for shore. A multitude flocking thither from all parts, received the bishops, whose coming had been foretold by the predictions even of their adversaries. For the evil spirits declared their fear, and when the bishops expelled them from the bodies of the possessed, they made known the nature of the tempest, and the dangers they had occasioned, and confessed that they had been overcome by the merits and authority of these men.

In the meantime the bishops speedily filled the island of Britain with the fame of their preaching and miracles; and the Word of God was by them daily preached, not only in the churches, but even in the streets and fields, so that the faithful and Catholic were everywhere confirmed, and those who had been perverted accepted the way of amendment. Like the Apostles, they acquired honour and authority through a good conscience, learning through the study of letters, and the power of working miracles through their merits. Thus the whole country readily came over to their way of thinking; the authors of the erroneous belief kept themselves in hiding, and, like evil spirits, grieved for the loss of the people that were rescued from them. At length, after long deliberation, they had the boldness to enter the lists. They came forward in all the splendour of their wealth, with gorgeous apparel, and supported by a numerous following; choosing rather to hazard the contest, than to undergo among the people whom they had led astray, the reproach of having been silenced, lest they should seem by saying nothing to condemn themselves. An immense multitude had been attracted thither with their wives and children. The people were present as spectators and judges; the two parties stood there in very different case; on the one side was Divine faith, on the other human presumption; on the one side piety, on the other pride; on the one side Pelagius, the founder of their faith, on the other Christ. The blessed bishops permitted their adversaries to speak first, and their empty speech long took up the time and filled the ears with meaningless words. Then the venerable prelates poured forth the torrent of their eloquence and showered upon them the words of Apostles and Evangelists, mingling the Scriptures with their own discourse and supporting their strongest assertions by the testimony of the written Word. Vainglory was vanquished and unbelief refuted; and the heretics, at every argument put before them, not being able to reply, confessed their errors. The people, giving judgement, could scarce refrain from violence, and signified their verdict by their acclamations.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Sep 2, 2011 | Ecclesiastical History of England

AS they were returning thence, the treacherous enemy, having, as it chanced, prepared a snare, caused Germanus to bruise his foot by a fall, not knowing that, as it was with the blessed Job, his merits would be but increased by bodily affliction. Whilst he was thus detained some time in the same place by his infirmity, a fire broke out in a cottage neighbouring to that in which he was; and having burned down the other houses which were thatched with reed, fanned by the wind, was carried on to the dwelling in which he lay. The people all flocked to the prelate, entreating that they might lift him in their arms, and save him from the impending danger. But he rebuked them, and in the assurance of his faith, would not suffer himself to be removed. The whole multitude, in terror and despair, ran to oppose the conflagration; but, for the greater manifestation of the Divine power, whatsoever the crowd endeavoured to save, was destroyed; and what the sick and helpless man defended, the flame avoided and passed by, though the house that sheltered the holy man lay open to it, and while the fire raged on every side, the place in which he lay appeared untouched, amid the general conflagration. The multitude rejoiced at the miracle, and was gladly vanquished by the power of God. A great crowd of people watched day and night before the humble cottage; some to have their souls healed, and some their bodies. All that Christ wrought in the person of his servant, all the wonders the sick man performed cannot be told. Moreover, he would suffer no medicines to be applied to his infirmity; but one night he saw one clad in garments as white as snow, standing by him, who reaching out his hand, seemed to raise him up, and ordered him to stand firm upon his feet; from which time his pain ceased, and he was so perfectly restored, that when the day came, with good courage he set forth upon his journey.

Next: How the same Bishops brought help from Heaven to the Britons in a battle, and then returned home.

Index

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Sep 1, 2011 | Ecclesiastical History of England

AT this time, that is, in the year of our Lord 605, the blessed Pope Gregory, after having most gloriously governed the Roman Apostolic see thirteen years, six months, and ten days, died, and was translated to an eternal abode in the kingdom of Heaven. Of whom, seeing that by his zeal he converted our nation, the English, from the power of Satan to the faith of Christ, it behoves us to discourse more at large in our Ecclesiastical History, for we may rightly, nay, we must, call him our apostle; because, as soon as he began to wield the pontifical power over all the world, and was placed over the Churches long before converted to the true faith, he made our nation, till then enslaved to idols, the Church of Christ, so that concerning him we may use those words of the Apostle; “if he be not an apostle to others, yet doubtless he is to us; for the seal of his apostleship are we in the Lord.”

He was by nation a Roman, son of Gordianus, tracing his descent from ancestors that were not only noble, but religious. Moreover Felix, once bishop of the same Apostolic see, a man of great honour in Christ and in the Church, was his forefather, Nor did he show his nobility in religion by less strength of devotion than his parents and kindred. But that nobility of this world which was seen in him, by the help of the Divine Grace, he used only to gain the glory of eternal dignity; for soon quitting his secular habit, he entered a monastery, wherein he began to live with so much grace of perfection that (as he was wont afterwards with tears to testify) his mind was above all transitory things; that he rose superior to all that is subject to change; that he used to think of nothing but what was heavenly; that, whilst detained by the body, he broke through the bonds of the flesh by contemplation; and that he even loved death, which is a penalty to almost all men, as the entrance into life, and the reward of his labours. This he used to say of himself, not to boast of his progress in virtue, but rather to bewail the falling off which he imagined he had sustained through his pastoral charge. Indeed, once in a private conversation with his deacon, Peter, after having enumerated the former virtues of his soul, he added sorrowfully, “But now, on account of the pastoral charge, it is entangled with the affairs of laymen, and, after so fair an appearance of inward peace, is defiled with the dust of earthly action. And having wasted itself on outward things, by turning aside to the affairs of many men, even when it desires the inward things, it returns to them undoubtedly impaired. I therefore consider what I endure, I consider what I have lost, and when I behold what I have thrown away; that which I bear appears the more grievous.”

So spake the holy man constrained by his great humility. But it behoves us to believe that he lost nothing of his monastic perfection by reason of his pastoral charge, but rather that he gained greater profit through the labour of converting many, than by the former calm of his private life, and chiefly because, whilst holding the pontifical office, he set about organizing his house like a monastery. And when first drawn from the monastery, ordained to the ministry of the altar, and sent to Constantinople as representative of the Apostolic see, though he now took part in the secular affairs of the palace, yet he did not abandon the fixed course of his heavenly life; for some of the brethren of his monastery, who had followed him to the royal city in their brotherly love, he employed for the better observance of monastic rule, to the end that at all times, by their example, as he writes himself, he might be held fast to the calm shore of prayer, as it were, with the cable of an anchor, whilst he should be tossed up and down by the ceaseless waves of worldly affairs; and daily in the intercourse of studious reading with them, strengthen his mind shaken with temporal concerns. By their company he was not only guarded against the assaults of the world, but more and more roused to the exercises of a heavenly life.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.