by Moe | Mar 4, 2013 | Meaning of Symbols

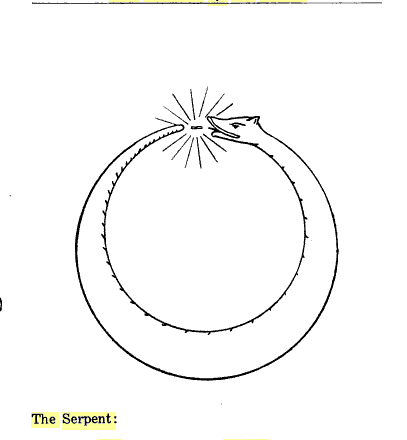

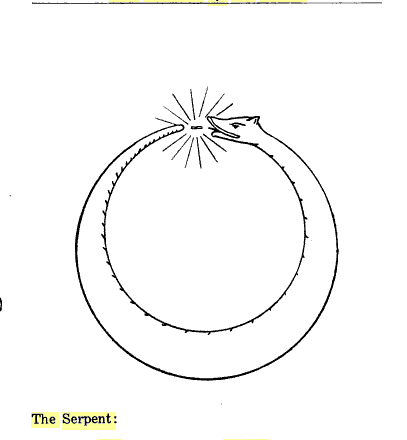

This is the serpent crown of the ancient Gods. It shows that the two paths or parts of the spirit fire have been united. This crown is the symbol of mastery and the union takes place within the student when the life forces are lifted to the brain. – Manly P. Hall

This is the serpent crown of the ancient Gods. It shows that the two paths or parts of the spirit fire have been united. This crown is the symbol of mastery and the union takes place within the student when the life forces are lifted to the brain. – Manly P. Hall

Since the most ancient times in history, the symbolical worship of the serpent has been seen world wide and is found everywhere, from here in America, to ancient Babylonia, Assyria, Mesopotamia, Persia, India, Cachmere, China, Japan, Arabia, Syria, Colchis, and Asia Minor. Since the dawn of recorded human time, many of our ancestors had recorded their adoration of the serpent in stone, onto walls and on paper. Without a doubt it is one of the most ancient and widely accepted symbols of spiritual wisdom that has ever been in existence.

The serpent in most all cultures has a similar meaning and is generally accepted as a symbol of divine wisdom and spiritual purity. In Gnosticism, the serpent represents eternity of the soul of the world and in the Gnostic text Pistis Sophia it describes the disc of the sun as a 12-part dragon with his tail in his mouth. Helena Blavatsy says that serpent worship was spread across the globe by “the Masters of Wisdom, and that all Initiates into the Sacred Mysteries, are called Nagas, or Serpents of Wisdom.

Alexander the Great, before he had become the son of Jupiter Ammon in the Siwa Oasis, was said to be the son of a serpent. Augustus Caesar’s mother Atia in legend had Augustus from a serpent and Scipio Africanus was said that he believed he was the son of a snake. (more…)

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 561

The essence of the ψυχικοὶ [psuchikoi] is disruption into multiplicity, manifoldness; which, however, is subordinate to a higher unity, by which it allows itself to be guided, first unconsciously, then consciously.

The essence of the ὑλικοὶ [Hulikoi] (of whom Satan is the head), is the direct opposite to all unity; disruption and disunion in itself, without the least sympathy, without any point of coalescence whatever for unity; together with an effort to destroy all unity, to extend its own inherent disunion to everything, and to rend everything asunder. This principle has no power to posit anything; but only to negative: it is unable to create, to produce, to form, but only to destroy, to decompose.

By Marcus, the disciple of Valentinus, the idea of a Λογος του οντος [Logos Tou Ontos], of a WORD, manifesting the hidden Divine Essence, in the Creation, was spun out into the most subtle details–the entire creation being, in his view, a continuous utterance of the Ineffable. The way in which the germs of divine life [the σπέρματα πνευματικὰ . . spermata pneumatika], which lie shut up in the Eons, continually unfold and individualize themselves more and more, is represented as a spontaneous analysis of the several names of the Ineffable, into their several sounds. An echo of the Ple_roma falls down into the ὕλη [Hule_], and becomes the forming of a new but lower creation.

One formula of the pneumatical baptism among the Gnostics ran thus: “In the NAME which is hidden from all the Divinities and Powers” [of the Demiurge], “The Name of Truth” [the Αλήθεια [Aletheia], self-manifestation of the Buthos], which Jesus of Nazareth has put on in the light-zones of Christ, the living Christ, through the Holy Ghost, for the redemption of the angels,–the Name by which all things attain to Perfection.” The candidate then said: “I am established and redeemed; I am redeemed in my soul from this world, and from all that belongs to it, by the name of ו ?Y?H?W?H, who has redeemed the Soul of Jesus by the living Christ.” The assembly then said: “Peace (or Salvation) to all on whom this name rests!”

The boy Dionusos, torn in pieces, according to the Bacchic Mysteries, by the Titans, was considered by the Manicheans as simply representing the Soul, swallowed up by the powers of darkness,–the

p. 562

divine life rent into fragments by matter:–that part of the luminous essence of the primitive man [the πρῶτος ἄνθρωπος [Protos Anthropos] of Mani, the πράων ἄνθρωπος [Prao_n Anthro_pos] of the Valentinians, the Adam Kadmon of the Kabalah; and the Kaiomorts of the Zendavesta], swallowed up by the powers of darkness; the Mundane Soul, mixed with matter–the seed of divine life, which had fallen into matter, and had thence to undergo a process of purification and development.

The Γνῶσις [Gnosis] of Carpocrates and his son Epiphanes consisted in the knowledge of one Supreme Original being, the highest unity, from whom all existence has emanated, and to whom it strives to return. The finite spirits that rule over the several portions of the Earth, seek to counteract this universal tendency to unity; and from their influence, their laws, and arrangements, proceeds all that checks, disturbs, or limits the original communion, which is the basis of nature, as the outward manifestation of that highest Unity. These spirits, moreover, seek to retain under their dominion the souls which, emanating from the highest Unity, and still partaking of its nature, have lapsed into the corporeal world, and have there been imprisoned in bodies, in order, under their dominion, to be kept within the cycle of migration. From these finite spirits, the popular religions of different nations derive their origin. But the souls which, from a reminiscence of their former condition, soar upward to the contemplation of that higher Unity, reach to such perfect freedom and repose, as nothing afterward can disturb or limit, and rise superior to the popular deities and religions. As examples of this sort, they named Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and Christ. They made no distinction between the latter and the wise and good men of every nation. They taught that any other soul which could soar to the same height of contemplation, might be regarded as equal with Him.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 543

Baptism was one of their most important ceremonies; and the Basilideans celebrated the 10th of January, as the anniversary of the day on which Christ was baptized in Jordan.

They had the ceremony of laying on of hands, by way of purification; and that of the mystic banquet, emblem of that to which they believed the Heavenly Wisdom would one day admit them, in the fullness of things [Πλήρωμα].

Their ceremonies were much more like those of the Christians than those of Greece; but they mingled with them much that was borrowed from the Orient and Egypt: and taught the primitive truths, mixed with a multitude of fantastic errors and fictions.

The discipline of the secret was the concealment (occultatio) of certain tenets and ceremonies. So says Clemens of Alexandria.

To avoid persecution, the early Christians were compelled to use great precaution, and to hold meetings of the Faithful [of the Household of Faith] in private places, under concealment by darkness. They assembled in the night, and they guarded against the intrusion of false brethren and profane persons, spies who might cause their arrest. They conversed together figuratively, and by the use of symbols, lest cowans and eavesdroppers might overhear: and there existed among them a favored class, or Order, who were initiated into certain Mysteries which they were bound by solemn promise not to disclose, or even converse about, except with such as had received them under the same sanction. They were called Brethren, the Faithful, Stewards of the Mysteries, Superintendents, Devotees of the Secret, and ARCHITECTS.

In the Hierarchiæ, attributed to St. Dionysius the Areopagite, the first Bishop of Athens, the tradition of the sacrament is said to have been divided into three Degrees, or grades, purification, initiation, and accomplishment or perfection; and it mentions also, as part of the ceremony, the bringing to sight.

The Apostolic Constitutions, attributed to Clemens, Bishop of Rome, describe the early church, and say: “These regulations must on no account be communicated to all sorts of persons, because of the Mysteries contained in them.” They speak of the Deacon’s duty to keep the doors, that none uninitiated should enter at the oblation. Ostiarii, or doorkeepers, kept guard, and gave notice of the time of prayer and church-assemblies; and also by private

p. 544

signal, in times of persecution, gave notice to those within, to en-able them to avoid danger. The Mysteries were open to the Fideles or Faithful only; and no spectators were allowed at the communion.

Tertullian, who died about A. D. 216, says in his Apology: “None are admitted to the religious Mysteries without an oath of secrecy. We appeal to your Thracian and Eleusinian Mysteries; and we are especially bound to this caution, because if we prove faithless, we should not only provoke Heaven, but draw upon our heads the utmost rigor of human displeasure. And should strangers betray us? They know nothing but by report and hearsay. Far hence, ye Profane! is the prohibition from all holy Mysteries.”

Clemens, Bishop of Alexandria, born about A. D. 191, says, in his Stromata, that he cannot explain the Mysteries, because he should thereby, according to the old proverb, put a sword into the hands of a child. He frequently compares the Discipline of the Secret with the heathen Mysteries, as to their internal and recondite wisdom.

Whenever the early Christians happened to be in company with strangers, more properly termed the Profane, they never spoke of their sacraments, but indicated to one another what they meant by means of symbols and secret watchwords, disguisedly, and as by direct communication of mind with mind, and by enigmas.

Origen, born A. D. 134 or 135, answering Celsus, who had objected that the Christians had a concealed doctrine said: “Inasmuch as the essential and important doctrines and principles of Christianity are openly taught, it is foolish to object that there are other things that are recondite; for this is common to Christian discipline with that of those philosophers in whose teaching some things were exoteric and some esoteric: and it is enough to say that it was so with some of the disciples of Pythagoras.”

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 261

the publicans, justice, equity, and fair dealing; the soldiery, peace, truth, and contentment; to do violence to none, accuse none falsely, and be content with their pay. He inculcated the necessity of a virtuous life, and the folly of trusting to their descent from Abraham.

He denounced both Pharisees and Sadducees as a generation of vipers, threatened with the anger of God. He baptized those who confessed their sins. He preached in the desert; and therefore in the country where the Essenes lived, professing the same doctrines. He was imprisoned before Christ began to preach. Matthew mentions him without preface or explanation; as if, apparently, his history was too well known to need any. “In those days,” he says, “came John the Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea.” His disciples frequently fasted; for we find them with the Pharisees coming to Jesus to inquire why His Disciples did not fast as often as they; and He did not denounce them, as His habit was to denounce the Pharisees; but answered them kindly and gently.

From his prison, John sent two of his disciples to inquire of Christ: “Art thou he that is to come, or do we look for another?” Christ referred them to his miracles as an answer; and declared to the people that John was a prophet, and more than a prophet, and that no greater man had ever been born; but that the humblest Christian was his superior. He declared him to be Elias, who was to come.

John had denounced to Herod his marriage with his brother’s wife as unlawful; and for this he was imprisoned, and finally executed to gratify her. His disciples buried him; and Herod and others thought he had risen from the dead and appeared again in the person of Christ. The people all regarded John as a prophet; and Christ silenced the Priests and Elders by asking them whether he was inspired. They feared to excite the anger of the people by saying that he was not. Christ declared that he came “in the way of righteousness”; and that the lower classes believed him, though the Priests and Pharisees did not.

Thus John, who was often consulted by Herod, and to whom that monarch showed great deference, and was often governed by his advice; whose doctrine prevailed very extensively among the people and the publicans, taught some creed older than Christianity. That is plain: and it is equally plain, that the very large

p. 262

body of the Jews that adopted his doctrines, were neither Pharisees nor Sadducees, but the humble, common people. They must, therefore, have been Essenes. It is plain, too, that Christ applied for baptism as a sacred rite, well known and long practiced. It was becoming to him, he said, to fulfill all righteousness.

In the 18th chapter of the Acts of the Apostles we read thus: “And a certain Jew, named Apollos, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man, and mighty in the Scriptures, came to Ephesus. This man was instructed in the way of the Lord, and, being fervent in spirit, he spake and taught diligently the things of the Lord, knowing only the baptism of John; and he began to speak boldly in the synagogue; whom, when Aquilla and Priscilla had heard, they took him unto them, and expounded unto him the way of God more perfectly.”

Translating this from the symbolic and figurative language into the true ordinary sense of the Greek text, it reads thus: “And a certain Jew, named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, and of extensive learning, came to Ephesus. He had learned in the mysteries the true doctrine in regard to God; and, being a zealous enthusiast, he spoke and taught diligently the truths in regard to the Deity, having received no other baptism than that of John.” He knew nothing in regard to Christianity; for he had resided in Alexandria, and had just then come to Ephesus; being, probably, a disciple of Philo, and a Therapeut.

“That, in all times,” says St. Augustine, “is the Christian religion, which to know and follow is the most sure and certain health, called according to that name, but not according to the thing itself, of which it is the name; for the thing itself, which is now called the Christian religion, really was known to the Ancients, nor was wanting at any time from the beginning of the human race, until the time when Christ came in the flesh; from whence the true religion, which had previously existed, began to be called Christian; and this in our days is the Christian religion, not as having been wanting in former times, but as having, in later times, received this name.” The disciples were first called “Christians,” at Antioch, when Barnabas and Paul began to preach there.

by Moe | Aug 26, 2011 | Morals and Dogma

p. 246

THIS is the first of the Philosophical Degrees of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite; and the beginning of a course of instruction which will fully unveil to you the heart and inner mysteries of Masonry. Do not despair because you have often seemed on the point of attaining the inmost light, and have as often been disappointed. In all time, truth has been hidden under symbols, and often under a succession of allegories: where veil after veil had to be penetrated before the true Light was reached, and the essential truth stood revealed. The Human Light is but an imperfect reflection of a ray of the Infinite and Divine.

We are about to approach those ancient Religions which once

p. 247

ruled the minds of men, and whose ruins encumber the plains of the great Past, as the broken columns of Palmyra and Tadmor lie bleaching on the sands of the desert. They rise before us, those old, strange, mysterious creeds and faiths, shrouded in the mists of antiquity, and stalk dimly and undefined along the line which divides Time from Eternity; and forms of strange, wild, startling beauty mingled in the vast throngs of figures with shapes monstrous, grotesque, and hideous.

The religion taught by Moses, which, like the laws of Egypt, enunciated the principle of exclusion, borrowed, at every period of its existence, from all the creeds with which it came in contact. While, by the studies of the learned and wise, it enriched itself with the most admirable principles of the religions of Egypt and Asia, it was changed, in the wanderings of the People, by everything that was most impure or seductive in the pagan manners and superstitions. It was one thing in the times of Moses and Aaron, another in those of David and Solomon, and still another in those of Daniel and Philo.

At the time when John the Baptist made his appearance in the desert, near the shores of the Dead Sea, all the old philosophical and religious systems were approximating toward each other. A general lassitude inclined the minds of all toward the quietude of that amalgamation of doctrines for which the expeditions of Alexander and the more peaceful occurrences that followed, with the establishment in Asia and Africa of many Grecian dynasties and a great number of Grecian colonies, had prepared the way. After the intermingling of different nations, which resulted from the wars of Alexander in three-quarters of the globe, the doctrines of Greece, of Egypt, of Persia, and of India, met and intermingled everywhere. All the barriers that had formerly kept the nations apart, were thrown down; and while the People of the West readily connected their faith with those of the East, those of the Orient hastened to learn the traditions of Rome and the legends of Athens. While the Philosophers of Greece, all (except the disciples of Epicurus) more or less Platonists, seized eagerly upon the beliefs and doctrines of the East,–the Jews and Egyptians, before then the most exclusive of all peoples, yielded to that eclecticism which prevailed among their masters, the Greeks and Romans.

Under the same influences of toleration, even those who embraced Christianity, mingled together the old and the new, Christianity

p. 248

and Philosophy, the Apostolic teachings and the traditions of Mythology. The man of intellect, devotee of one system, rarely displaces it with another in all its purity. The people take such a creed as is offered them. Accordingly, the distinction between the esoteric and the exoteric doctrine, immemorial in other creeds, easily gained a foothold among many of the Christians; and it was held by a vast number, even during the preaching of Paul, that the writings of the Apostles were incomplete; that they contained only the germs of another doctrine, which must receive from the hands of philosophy, not only the systematic arrangement which was wanting, but all the development which lay concealed therein. The writings of the Apostles, they said, in addressing themselves to mankind in general, enunciated only the articles of the vulgar faith; but transmitted the mysteries of knowledge to superior minds, to the Elect,–mysteries handed down from generation to generation in esoteric traditions; and to this science of the mysteries they gave the name of Γνῶσις; [Gnosis].

This is the serpent crown of the ancient Gods. It shows that the two paths or parts of the spirit fire have been united. This crown is the symbol of mastery and the union takes place within the student when the life forces are lifted to the brain. – Manly P. Hall

This is the serpent crown of the ancient Gods. It shows that the two paths or parts of the spirit fire have been united. This crown is the symbol of mastery and the union takes place within the student when the life forces are lifted to the brain. – Manly P. Hall