Meekness marked the attitude of the Stoic philosopher. While Diogenes was delivering a discourse against anger, one of his listeners spat contemptuously in his face. Receiving the insult with humility, the great Stoic was moved to retort: “I am not angry, but am in doubt whether I ought to be so or not!”

Epicurus of Samos (341-270 B.C.) was the founder of the Epicurean sect, which in many respects resembles the Cyrenaic but is higher in its ethical standards. The Epicureans also posited pleasure as the most desirable state, but conceived it to be a grave and dignified state achieved through renunciation of those mental and emotional inconstancies which are productive of pain and sorrow. Epicurus held that as the pains of the mind and soul are more grievous than those of the body, so the joys of the mind and soul exceed those of the body. The Cyrenaics asserted pleasure to be dependent upon action or motion; the Epicureans claimed rest or lack of action to be equally productive of pleasure. Epicurus accepted the philosophy of Democritus concerning the nature of atoms and based his physics upon this theory. The Epicurean philosophy may be summed up in four canons:

“(1) Sense is never deceived; and therefore every sensation and every perception of an appearance is true. (2) Opinion follows upon sense and is superadded to sensation, and capable of truth or falsehood, (3) All opinion attested, or not contradicted by the evidence of sense, is true. (4) An opinion contradicted, or not attested by the evidence of sense, is false.” Among the Epicureans of note were Metrodorus of Lampsacus, Zeno of Sidon, and Phædrus.

Eclecticism may be defined as the practice of choosing apparently irreconcilable doctrines from antagonistic schools and constructing therefrom a composite philosophic system in harmony with the convictions of the eclectic himself. Eclecticism can scarcely be considered philosophically or logically sound, for as individual schools arrive at their conclusions by different methods of reasoning, so the philosophic product of fragments from these schools must necessarily be built upon the foundation of conflicting premises. Eclecticism, accordingly, has been designated the layman’s cult. In the Roman Empire little thought was devoted to philosophic theory; consequently most of its thinkers were of the eclectic type. Cicero is the outstanding example of early Eclecticism, for his writings are a veritable potpourri of invaluable fragments from earlier schools of thought. Eclecticism appears to have had its inception at the moment when men first doubted the possibility of discovering ultimate truth. Observing all so-called knowledge to be mere opinion at best, the less studious furthermore concluded that the wiser course to pursue was to accept that which appeared to be the most reasonable of the teachings of any school or individual. From this practice, however, arose a pseudo-broadmindedness devoid of the element of preciseness found in true logic and philosophy.

The Neo-Pythagoreanschool flourished in Alexandria during the first century of the Christian Era. Only two names stand out in connection with it–Apollonius of Tyana and Moderatus of Gades. Neo-Pythagoreanism is a link between the older pagan philosophies and Neo-Platonism. Like the former, it contained many exact elements of thought derived from Pythagoras and Plato; like the latter, it emphasized metaphysical speculation and ascetic habits. A striking similarity has been observed by several authors between Neo-Pythagoreanism and the doctrines of the Essenes. Special emphasis was laid upon the mystery of numbers, and it is possible that the Neo-Pythagoreans had a far wider knowledge of the true teachings of Pythagoras than is available today. Even in the first century Pythagoras was regarded more as a god than a man, and the revival of his philosophy was resorted to apparently in the hope that his name would stimulate interest in the deeper systems of learning. But Greek philosophy had passed the zenith of its splendor; the mass of humanity was awakening to the importance of physical life and physical phenomena. The emphasis upon earthly affairs which began to assert itself later reached maturity of expression in twentieth century materialism and commercialism,

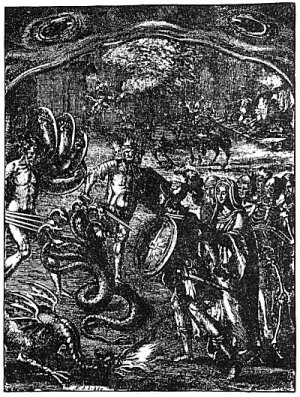

ÆNEAS AT THE GATE OF HELL.

From Virgil’s Æneid. (Dryden’s translation.) Virgil describes part of the ritual of a Greek Mystery–possibly the Eleusinian–in his account of the descent of Æneas, to the gate of hell under the guidance of the Sibyl. Of that part of the ritual portrayed above the immortal poet writes:

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.