In this age the word philosophy has little meaning unless accompanied by some other qualifying term. The body of philosophy has been broken up into numerous isms more or less antagonistic, which have become so concerned with the effort to disprove each other’s fallacies that the sublimer issues of divine order and human destiny have suffered deplorable neglect. The ideal function of philosophy is to serve as the stabilizing influence in human thought. By virtue of its intrinsic nature it should prevent man from ever establishing unreasonable codes of life. Philosophers themselves, however, have frustrated the ends of philosophy by exceeding in their woolgathering those untrained minds whom they are supposed to lead in the straight and narrow path of rational thinking. To list and classify any but the more important of the now recognized schools of philosophy is beyond the space limitations of this volume. The vast area of speculation covered by philosophy will be appreciated best after a brief consideration of a few of the outstanding systems of philosophic discipline which have swayed the world of thought during the last twenty-six centuries. The Greek school of philosophy had its inception with the seven immortalized thinkers upon whom was first conferred the appellation of Sophos, “the wise.” According to Diogenes Laertius, these were Thales, Solon, Chilon, Pittacus, Bias, Cleobulus, and Periander. Water was conceived by Thales to be the primal principle or element, upon which the earth floated like a ship, and earthquakes were the result of disturbances in this universal sea. Since Thales was an Ionian, the school perpetuating his tenets became known as the Ionic. He died in 546 B.C., and was succeeded by Anaximander, who in turn was followed by Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, and Archelaus, with whom the Ionic school ended. Anaximander, differing from his master Thales, declared measureless and indefinable infinity to be the principle from which all things were generated. Anaximenes asserted air to be the first element of the universe; that souls and even the Deity itself were composed of it.

Anaxagoras (whose doctrine savors of atomism) held God to be an infinite self-moving mind; that this divine infinite Mind, not

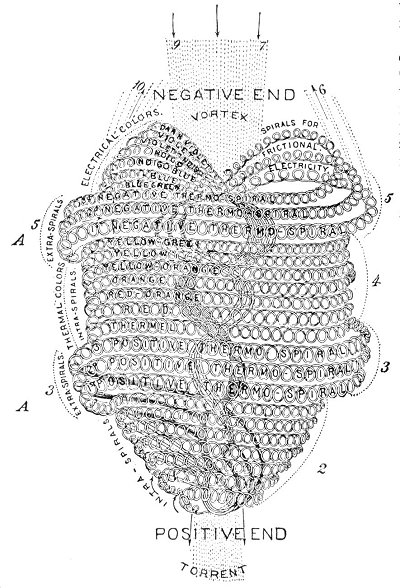

BABBITT’S ATOM.

From Babbitt’s Principles of Light and Color. Since the postulation of the atomic theory by Democritus, many efforts have been made to determine the structure of atoms and the method by which they unite to form various elements, Even science has not refrained from entering this field of speculation and presents for consideration most detailed and elaborate representations of these minute bodies. By far the most remarkable conception of the atom evolved during the last century is that produced by the genius of Dr. Edwin D. Babbitt and which is reproduced herewith. The diagram is self-explanatory. It must be borne in mind that this apparently massive structure is actually s minute as to defy analysis. Not only did Dr. Babbitt create this form of the atom but he also contrived a method whereby these particles could be grouped together in an orderly manner and thus result in the formation of molecular bodies.

p. 14

inclosed in any body, is the efficient cause of all things; out of the infinite matter consisting of similar parts, everything being made according to its species by the divine mind, who when all things were at first confusedly mingled together, came and reduced them to order.” Archelaus declared the principle of all things to be twofold: mind (which was incorporeal) and air (which was corporeal), the rarefaction and condensation of the latter resulting in fire and water respectively. The stars were conceived by Archelaus to be burning iron places. Heraclitus (who lived 536-470 B.C. and is sometimes included in the Ionic school) in his doctrine of change and eternal flux asserted fire to be the first element and also the state into which the world would ultimately be reabsorbed. The soul of the world he regarded as an exhalation from its humid parts, and he declared the ebb and flow of the sea to be caused by the sun.

After Pythagoras of Samos, its founder, the Italic or Pythagorean school numbers among its most distinguished representatives Empedocles, Epicharmus, Archytas, Alcmæon, Hippasus, Philolaus, and Eudoxus. Pythagoras (580-500? B.C.) conceived mathematics to be the most sacred and exact of all the sciences, and demanded of all who came to him for study a familiarity with arithmetic, music, astronomy, and geometry. He laid special emphasis upon the philosophic life as a prerequisite to wisdom. Pythagoras was one of the first teachers to establish a community wherein all the members were of mutual assistance to one another in the common attainment of the higher sciences. He also introduced the discipline of retrospection as essential to the development of the spiritual mind. Pythagoreanism may be summarized as a system of metaphysical speculation concerning the relationships between numbers and the causal agencies of existence. This school also first expounded the theory of celestial harmonics or “the music of the spheres.” John Reuchlin said of Pythagoras that he taught nothing to his disciples before the discipline of silence, silence being the first rudiment of contemplation. In his Sophist, Aristotle credits Empedocles with the discovery of rhetoric. Both Pythagoras and Empedocles accepted the theory of transmigration, the latter saying: “A boy I was, then did a maid become; a plant, bird, fish, and in the vast sea swum.” Archytas is credited with invention of the screw and the crane. Pleasure he declared to be a pestilence because it was opposed to the temperance of the mind; he considered a man without deceit to be as rare as a fish without bones.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.