by Moe | Jan 31, 2024 | Meaning of Symbols, Meaning of Words, Philosophy

Since ancient times, many philosophers, mathematicians, and theologians have said that the monad or number one represents a secret principle of a sacred central fire that unites all things forming our realities.

This concept has a profound significance in both philosophy and cosmogony for well over 2,000 years.

The Greeks called it the “monad or monas,” meaning “unity” or “oneness,” which represents the fundamental building block of existence. It was associated with the belief in the “prime mover” or the first cause that set the universe in motion.

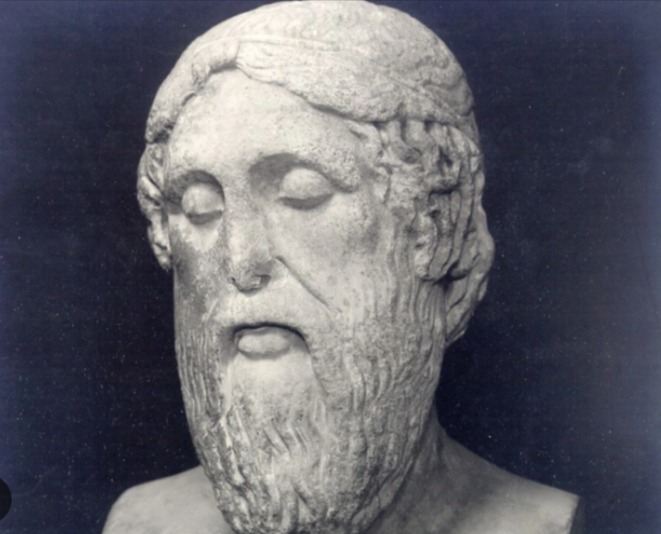

This concept can be traced back to the teachings of ancient philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato, who believed in the existence of a fundamental substance that underlies the diversity of the material world.

According to Pythagoras, who some consider the Father of Math and his followers, the Pythagoreans, the monad is the ultimate source of all existence.

In this philosophy, the number one or monad is considered the origin of numbers, as numbers are seen as the building blocks of reality. It stood at the pinnacle of this numerical hierarchy.

For the Pythagoreans, the Monad represented the source from which all other numbers and mathematical relationships were derived.

It symbolized unity, indivisibility, and the essence of all beings.

ORDO AB CHAO

The monad is seen as the creative force, fire or energenetic force that brings order out of chaos, giving rise to the intricate web of interconnectedness that defines our reality. It is the principle that brings about the principles of symmetry, proportion, and harmony that permeate the natural world.

In Pythagorean cosmogony, it serves as the guiding force that organizes or more appropriately, magnetizes the chaotic elements of the universe into a harmonious order. According to their teachings, each number possessed its own unique essence and vibrational frequency, and these vibrations were considered to be the very fabric of reality.

They believed that it gave rise to the dyad, which then generated all other numbers and the material world. It is the indivisible and immutable essence that underlies the entire cosmos.

This embodies the idea that everything in the universe can be reduced to a singular, fundamental unit. In its essence, it is the ultimate unity, the indivisible entity from which all things originate. Hence, the monad represents the primary building block of reality, the seed of creation, and the spark that ignites the cosmic order.

For Plato, this force or fire was called ether and was the substance by which the Craftsmam had created the universe and world. The Freemasons represent this with their motto, ORDO AB CHAO and the concept of the Great Architect of the Universe (T.G.A.O.T.U.).

This concept of the monad is often depicted as a circle, symbolizing its perfect and infinite nature.

THE MONAD IN ESOTERIC PHILOSOPHY

In the realm of ancient and esoteric philosophies, the concept of the Monad holds a significant place in Gnosticism, Hermeticism and Alchemy. These mystical traditions, intertwined with deep spiritual wisdom, have long sought to understand the nature of existence and the interconnectedness of all things.

In Gnosticism, the monad is at the root of the pleroma, the infinite fount of matter and energy in the universe.

In Hermeticism, the Monad is seen as the ultimate source of all creation, the divine spark from which everything springs forth. It represents the timeless and indescribable essence that permeates all levels of reality. This concept aligns with the idea of the One in Neoplatonism, emphasizing the unity and oneness of the universe.

Alchemy, on the other hand, views the Monad as the primordial substance or the original matter from which the alchemical transmutation takes place. It is the raw material that undergoes various stages of refinement and purification, ultimately leading to the attainment of perfection or the Philosopher’s Stone.

It symbolizes the potential for transformation and the inherent unity of all elements.

33rd Degree Freemason and author, Manly P. Hall wrote;

“The number one was the point within the circle , and denoted the central fire , or God , because it is the beginning and ending ; the first and the last . It signified also love , concord , piety , and friendship , because it is so …”

Hall said, “The sun is a great dot, a monad of life, and each of its rays a line – its own active principle in manifestation.

The key thought is: The line is the motion of the dot. The dot, or Sacred Island, is the beginning of existence, whether that of a universe or a man.”

It is seen as the unity that precedes duality, representing the transition from the formless to the formed.

Just as the concept is a single entity, it is also considered the harmonious union of opposites. It represents the synthesis of opposites such as light and darkness, male and female, unity and multiplicity, and harmony, balance or order.

As Plato wrote, “Love is born into every human being; it calls back the halves of our original nature together; it tries to make one out of two and heal the wound of human nature.” (Plato, The Symposium)

From Plato, Neoplatonism, placed great emphasis on the concept of the Monad, particularly through the teachings of one of its prominent figures, Plotinus.

According to Plotinus, the One is beyond all categories and distinctions. It is ineffable and transcendent, beyond the grasp of human comprehension. It is the origin and cause of all things, the pure essence from which everything else derives its being.

Plotinus taught that through contemplation and philosophical inquiry, individuals can come to realize their connection to the One and experience a sense of oneness with the ultimate reality.

In Neoplatonic philosophy, the journey towards understanding the One, or the Monad, is seen as a spiritual ascent. This journey involves transcending the limitations of the material world and ascending through the various levels of existence, ultimately reaching a state of unity with the One.

This realization brings about a transformative spiritual awakening, leading to a higher understanding of the self and the universe.

THE MONAD IN EASTERN PHILOSOPHY

In Chinese philosophy, the concept of the monad is reflected in the teachings of Taoism, where it represents the ultimate source of all things. Taoism, rooted in the profound wisdom of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, delves into the fundamental principles of existence and the interconnectedness of all things.

At the heart of Taoist philosophy lies the concept of the Tao, often described as the “Way” or the “Ultimate Reality.”

It is the underlying force that governs the universe, encompassing both the seen and unseen aspects of existence representing the unifying essence that flows through all things, connecting them in a harmonious and ever-evolving dance.

According to Taoist teachings, it is the eternal and unchanging essence that transcends the duality of existence, encompassing both yin and yang, darkness and light, movement and stillness.

The Taoist sages emphasize the importance of aligning oneself with the flow of the monad, harmonizing with its rhythms and embracing the natural order of the universe.

It was also explored in Indian philosophy, particularly in the school of Hindu philosophy known as Advaita Vedanta. Here, the monad, referred to as “Atman,” is considered the eternal, unchanging essence of the self, which is indistinguishable from the ultimate reality, known as “Brahman.”

This idea of the monad was incorporated within monotheism, and the monotheistic religions symbolized as God or the universe.

It served as a metaphorical representation of the divine spark present within every individual. The Monad was seen as the innermost essence of the human soul, connecting each individual to the universal cosmic order.

It embodied the idea that each person possessed a unique and irreplaceable role within the grand tapestry of existence.

Hence, One God. One Lord. One Faith and One Baptism by Holy Fire (monad) – Not water.

To reunite with the One of God was to be Born Again.

The Prodigal son who was lost is now found.

THE MONAD IN MODERN SCIENCE

In the field of science, the notion of a unified theory that explains the fundamental workings of the universe has been a longstanding pursuit.

From the Ancient Pythagoreans and Plato to Leibniz’s monadology and modern science and philosophy, the concept of the monad has provided the unifying framework for the theory of relativity to quantum mechanics, understanding consciousness, free will, and the nature of reality itself.

In the 17th century, German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz revived the concept of the monad. His magnum opus, “Monadology,” provides profound insights into the nature of reality, metaphysics, and the interconnectedness of all things.

In “Monadology,” Leibniz presents a metaphysical framework that explains the nature of existence and how monads relate to one another. He argues that they do not directly interact but rather harmoniously coexist in a pre-established harmony, orchestrated by a divine entity.

Leibniz’s modern concept of monadology challenges the traditional understanding of causality and suggests a synchronized universe where every monad’s actions align with the actions of other monads, creating a grand cosmic dance.

Influenced by his studies in mathematics and metaphysics, Leibniz proposed that monads were the basic units of reality, each possessing its own unique properties and experiences. He said they were indivisible and could not be influenced by external forces, but rather, they interacted with one another through a pre-established harmony.

According to Leibniz, they are indivisible, immaterial substances that are the fundamental building blocks of the universe.

Each is unique, representing a distinct perspective on reality.

These monads are not passive entities but rather possess inherent qualities and capacities that allow them to perceive, act, and interact with other monads.

He suggests that each one possesses a unique perception of the universe, which he calls “apperception.”

This individualistic perspective shapes the experiences and consciousness of each monad, making them active participants in the construction of reality. Hence, each individual substance is seen as a unique monad with its own perception and consciousness that are co-creators or builders of the world in which we live.

Epistemologically, Leibniz’s monads provide a unique perspective on the nature of knowledge or Gnosis.

Since each monad is a separate and distinct microcosm of the universe, it possesses its own unique perspective and experiences. This notion of “pre-established harmony” suggests that each monad has access to a specific set of truths, forming the basis of its individual knowledge.

Hence, no two humans are exactly the same.

Furthermore, Leibniz proposes that they are not confined to the physical realm but also exist in the realm of immaterial substances. This duality allows for a deeper exploration of the connection between mind and matter, challenging the Cartesian mind-body dualism prevalent during his time.

In the realm of physics, the concept of the Monad resonates with the fundamental building blocks of the universe. In particle physics, for instance, the notion of elementary particles can be seen as analogous to monads.

These indivisible units, such as quarks or electrons, possess unique properties and interact with one another to form the complexity we observe in the physical world.

In biology, the concept can be related to the idea of the cell as the fundamental unit of life. Just as monads are self-contained entities, cells possess their own internal structures and functions, while simultaneously interacting with other cells to compose the complex organisms we observe.

Moreover, the concept of the Monad has also sparked intriguing discussions in fields such as psychology and consciousness studies. Some theorists propose that the monad can be associated with the individual consciousness, representing a unique and self-contained center of experience within each person.

Additionally, the concept of monads has found resonance in cosmogony, the study of the origin and evolution of the universe. They are seen as the primordial entities that give rise to the diversity and complexity of the cosmos.

Monads represent the underlying fabric from which everything emerges and are seen as the driving force behind the dynamic unfolding of the universe.

In the realm of mathematics and computer science, the concept of the Monad has found its home in the paradigm of functional programming. Functional programming is an approach to software development that emphasizes the use of pure functions and immutable data.

In functional programming, a monad represents a computational context or a sequence of computations. In functional programming, it provides a clear separation between pure computations and impure actions, promoting code that is easier to reason about and test.

It allows developers to encapsulate side effects, such as reading from or writing to a database, handling exceptions, or dealing with I/O operations, within a controlled and composable structure. This enforces an explicit and disciplined mathematical approach to handling effects, ensuring that their impact is predictable and managed within the confines of the Monad.

At the core of the Monad in functional programming lies the bind operation, often represented by the symbol “>>=”, which allows sequential composition of computations within the Monad. This enables developers to chain together a series of operations, each dependent on the result of the previous one, without explicitly dealing with the underlying data transformations or side effects.

Hence, ALL IS MATH.

By leveraging the Monad, functional programmers can write code that is concise, modular, and reusable, which simplifies complex operations and promotes a declarative style of programming. It enables them to leverage the principles of functional programming to write elegant and efficient code, while also appreciating the historical and philosophical roots of this powerful concept.

Today we can see this in real time with social media platforms like X, Facebook and Instagram that are monotheistic hosts to billions of people, each living in their own multipolar worlds.

Worlds that are not defined by biological traits, genetics, and common characteristics, but by various degrees and categories of knowledge, ideas and wisdom or a lack thereof.

Let me remind you that in modern monadology, monads are individualistically magnetic and like attracts like.

This is why in the monotheistic religion of Christianity, the great teacher Jesus said;

“My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge: because thou hast rejected knowledge, I will also reject thee, that thou shalt be no priest to me: seeing thou hast forgotten the law of thy God, I will also forget thy children.” – Hosea 4:6

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the significance of monads in modern philosophy lies in their role as fundamental entities that shape our understanding of existence, consciousness, and the interconnected nature of reality.

It invites us to question the nature of the world as we contemplate the interplay between unity and multiplicity, and delve into the depths of our own existence.

As we embark on this monadic journey, we open ourselves to new insights and perspectives that can enrich our understanding of the profound mysteries within the cosmic tapestry (filamental web) that surrounds us.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Jan 23, 2024 | Brain, Mind Control Research, Philosophy

Brain waves, also known as brain rhythms or oscillations, emerge from the synchronized network of electrical activity of neurons in our brains. These coordinated efforts facilitate crucial functions like perception, cognition, and intelligence.

From our thoughts and emotions to our behavior and learning abilities, brain wave patterns play a crucial role in shaping who we are as individuals. In fact, studies have shown they hold the key to understanding the intricacies of human uniqueness.

The latest neuroscience research has found that our brains operate on differing frequencies, each associated with different states of consciousness and intelligent functions. What it shows is that each of us has differing brain wave activity that is directly related to our genetics and learning capabilities which equates to our overall intelligence and IQ.

Hence, your ability to truly think and your intelligence can now be measured and categorized into different frequencies, each associated with specific mental states and cognitive processes. Therefore, understanding the different types of brain waves is a fascinating and essential aspect of unraveling the mystery of how they define our uniqueness.

Scientists are able to assess human intelligence and mental illness with a special machine called an electroencephalogram (EEG). During an EEG, electrodes are placed on the scalp to detect and record brain waves, which are rhythmic oscillations of electrical activity that occur in different regions of the brain.

These electrodes pick up the different frequencies and amplitudes of the brain waves starting at the low delta (<4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), and higher frequencies such as beta (12-30 Hz), gamma (30–80 Hz), and high gamma (>80 Hz). The recorded data is then analyzed to identify the various types of waves and their patterns.

The unique combination and interplay of these brain wave patterns contribute to our individual uniqueness.

Just as no two fingerprints are exactly alike, no two individuals have the same brain wave patterns. These patterns shape our cognitive abilities, personality traits, and even our responses to external stimuli.

Research has shown that each of these waves corresponds to specific mental states and activities, offering insights into our cognitive processes and overall brain functioning.

For example, beta waves, which have a high frequency, are linked to focused attention, problem-solving, and critical thinking.

Alpha waves, with a lower frequency just under beta, are associated with a relaxed state of mind, creativity, and insight.

However, the highest cognitive functions in humans are measured via gamma waves, the fastest and highest frequency brain waves, which are linked to heightened cognitive functioning, attention, and memory.

These waves are believed to play a crucial role in learning and information processing, allowing us to absorb and retain new knowledge effectively.

But when it comes to people whose brains are not functioning properly or due to mental illness, they operate in the theta and delta range.

Slow wave activity is composed of both large amplitude and low frequency activity in the delta (0.5–4 Hz) or theta (4–7 Hz) frequency bands is normally only seen in people while they are sleeping, but it is also observed in people with mental illness.

Delta and theta activity in the waking state has mainly been studied in people with neurological disorders, but abnormal slow brain waves are found in many developmental and degenerative disorders, and also in several other neurological conditions.

Delta waves, characterized by low-frequency and high-amplitude patterns, are associated with deep sleep and unconsciousness. These waves are crucial for restorative sleep, allowing our bodies to rejuvenate and recharge during the night as we repair our bodily tissues, and strengthen the immune system.

This technology is being further developed by various governments for biometric security in the form of finger and palm prints, iris scanning, facial recognition, and blood, vein and cognitive pattern recognition.

The Four Types of Biometric Security are:

Biological biometrics

Morphological biometrics

Behavioral biometrics

Cognitive biometrics

Cognitive biometric security measures brainwave patterns, also known as brainprints, which are considered a superior biometric alternative by researchers when compared to fingerprints or retinal scans.

This is a novel approach to user authentication and/or identification that utilizes the response(s) of nervous tissue in response to one or more stimuli, and the subsequent response(s) are acquired and used for authentication.

Cognitive biometrics use bio-signals that are measured via a EEG-based BCI system for authenticating a person is primarily derived from the unique subtle features embedded in them (Revett and de Magalhães, 2010; Gupta et al., 2012).

Unlike fingerprints or retinas, which are static once compromised, a brainwave pattern offers the advantage of being changeable, enabling users to reset it if their brain print is stolen.

One of the key advantages of the brainprint is its non-invasive nature.

Unlike traditional biometric methods that rely on physical features like fingerprints or facial recognition, a brainprint does not require any direct contact with individuals.

This makes it convenient, user-friendly, and less susceptible to privacy concerns. Individuals can be recognized simply by analyzing their unique brain activity patterns, without the need for physical interaction.

Moreover, the complexity of brain patterns makes it extremely difficult for potential attackers to forge or replicate brainprints. The intricate network of neural connections and individual brain signatures add an extra layer of security to the system.

This resistance to attacks enhances the robustness and reliability of brainprint as a biometric recognition technology.

A 2016 study from Binghamton University used cognitive biometrics to identify a group of 50 participants with 100 percent accuracy. Previous research published in 2015 successfully identified individuals with 97 percent accuracy.

The significant improvement from 97 percent last year to a perfect 100 percent this year is particularly crucial for high-security environments like the Pentagon, necessitating flawless detection and authorization systems.

As neuroimaging and hidden biometric modalities continue to evolve, the brainprint emerges as a compelling alternative for person recognition.

Unraveling the mystery of how brain wave patterns define our uniqueness opens up a world of possibilities for harnessing our cognitive abilities to their fullest potential.

It highlights the intricate interplay between our brains and our individual cognitive strengths, providing a deeper understanding of what makes each of us truly unique.

SOURCES:

EEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security

Using brain prints as new biometric feature for human recognition

Digital Trends

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Dec 18, 2023 | Gnosis, Philosophy

“Now, God made the world for the sake of beings who were to be, as it were, co-workers with him in the creation of life.” – Plato

The ancient Greek philosopher, Plato had a profound understanding of the secret nature of reality, which he expressed in some of his most influential works such as “Timeaus.” It provides a unique perspective on the role of what he calls “the Craftsman”, also referred to as the “Demiurge” who possesses remarkable artistry and skill in shaping and creating the world.

Plato’s ideas of the demiurge take center stage as the creator responsible for shaping the physical realm we inhabit with purposeful intent.

This departure from traditional theological concepts of fate and hope challenges established notions of a supreme being that not only governs the universe, but every person’s consciousness. Unlike traditional religious beliefs attributing creation to a divine intelligence or a personal ruler, this perspective rejects the notion of creation as a purely metaphysical or abstract process undertaken by an all-powerful deity.

Another crucial aspect of his depiction of the Craftsman was the notion of purposeful creation.

Instead, Plato emphasizes the role of manual labor, skill, artistry, and purposeful creation as the driving forces behind the physical world. This perspective encourages us to reflect on the inherent order and harmony found within nature and the intricate interconnections between various elements of the cosmos and between all things – including human beings.

These ideas raise questions about the purpose and intention behind our existence and the role of the creator in shaping our minds and reality. As we delve deeper into Plato’s philosophy, we begin to question our preconceptions about what we know about the world and the nations and cultures we inhabit were truly created.

The Craftsman (Demiurge,” dêmiourgos, 28a6) is central to Plato’s philosophy in a dialogue between Socrates, Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates, in which they discuss various topics related to the nature of the universe. Timaeus, the main speaker in the dialogue, is a Pythagorean philosopher who argues that the Craftsman was both the creator and the ruler of the universe, responsible for the ongoing maintenance and perfection of all things.

The idea of the Craftsman is Plato’s explanation of Orphic mysteries with the God known as Theogonies Phanes – Zeus, the primordial God of creation who builds the world out of elemental or primordial matter. This concept has been very influential in philosophy, theology, science, and Freemasonry over the last two thousand-plus years.

For example, in the Abrahamic religions, God is the supreme deity who made the world and he guided human destiny and the idea of the Craftsman would align with Masonic concept of The Grand Architect of the Universe (T.G.A.O.T.U.).

Plato’s Craftsman also encompasses a wide range of scientific, metaphysical and epistemological ideas, all intricately intertwined within a concept he calls “Forms or Ideas.” This concept posits that the material world we perceive is but a mere reflection or imperfect copy of higher, eternal, and perfect forms.

These forms, according to Plato, exist in a transcendent realm beyond our physical reality.

His understanding of the Craftsman is deeply rooted in his metaphysics, which states that the world is made up of two distinct realms: the realm of Forms and the realm of the material world. Plato presents a cosmological account of the origin of the world with the Demiurge depicted as a skilled craftsman or artisan who utilizes pre-existing material and imitates the eternal Forms to shape the physical realm.

The realm of Forms is the realm of abstract concepts, such as beauty, justice, and goodness. The material world, on the other hand, is the world of physical objects that we can see, touch, and experience.

For Plato, the Craftsman was responsible for bridging the gap between these two realms.

Through the act of creation, the Craftsman brought the Forms into the material world, giving them shape and substance. This process of creation was not a one-time event but was continually shaping and perfecting the universe.

According to Plato, the Craftsman began by creating the world soul, which he describes as “the most divine and the most comprehensive of all things” (Timeaus 30b). The world soul is the animating force that gives life to the universe, providing the necessary energy for all things to exist and thrive.

As I have explained in previous essays, Plato’s world soul can be compared to the Freemasonic concept of The Grand Architect of the Universe and the All Seeing Eye. In the Abrahamic religions, we find this concept in the Eye of Providence and Heaven and in science as the Noosphere.

Plato argues that we can bring goodness and order to the world by shaping our lives to reflect the good because chaos is disturbing both physically and spiritually, It confuses our sense of the rightness and order of things.

Once the world soul was created, the Craftsman began to shape the physical world, starting with the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. These elements were not created ex nihilo but were instead formed from the preexisting chaos that existed before the universe was created.

The Craftsman then combined these elements to create the physical world, including the stars, planets, and all living things. The process of creation was not haphazard but followed a divine plan that was preordained.

He explains that the Craftsman/Demiurge used the four elements – fire, air, water, and earth – to create the world. Using the principles of proportion and harmony to create a universe that is ordered and beautiful. Timaeus explains:

“Now, in dealing with the universe, he mixed the unintelligible with the intelligible, and the result was a visible universe which was both beautiful and intelligent” (30a). Here, he is suggesting that the Craftsman is able to create an ordered and rational universe by combining intelligible principles with unintelligible matter.

“The creator made the world a living being, with soul and reason, because he was good and wise. He also made the world beautiful and good, because he desired that it should be like himself. He made the universe out of fire and earth, and he mixed them together in the proportion of two to one. He then added air and water in due proportion, and out of this mixture he formed a globe, which he divided into seven circles, which he called the seven planets.”

In other words, the Craftsman is able to bring order out of chaos by using his intellect and skill to shape the raw materials of the universe into a harmonious whole.

Furthermore, the Craftsman is not a passive or indifferent creator.

Rather, he is deeply invested in the well-being of the universe and takes an active role in its ongoing development and maintenance. In Timeaus, Plato wrote:

“For it was necessary that it should be made as beautiful as possible and as good as possible. Hence, he who was to be a good creator, inasmuch as he was good, fashioned the universe with beauty as well as goodness” (30a).

Here, Plato is suggesting that the Craftsman is motivated by a desire to create a universe that is not only ordered and rational but also beautiful and good.

The Craftsman’s Role in Human Life:

Plato’s concept of the Craftsman is not limited to the creation of the universe. Rather, it has important implications for human life as well.

In Timeaus, he writes: “Now, God made the world for the sake of beings who were to be, as it were, co-workers with him in the creation of life” (31a).

Here, Plato is suggesting that human beings have a special role to play in the ongoing development and maintenance of the world in which we live. Like the Craftsman, our nations and societies should belt by intelligent design and skillful labor in which we are are all workers cooperating with one another in its fabrication.

The Craftsman was a perfect being, free from imperfection and error, and his creation reflected this perfection. As Plato explains, “He [the Craftsman] was good, and in him there was no variation or inconsistency; for being changeless, he was the cause of consistency in everything” (Timeaus 29e).

Furthermore, the Craftsman is responsible for endowing human beings with the ability to reason and intelligence to understand the world around them.

It is the source of all motion for the universe as a whole, the World Soul, and the soul of humans.

Timaeus argues that this source must be an efficient cause (Timaeus 27d). An efficient cause, he says, is one that acts without being acted upon.

In other words, it does not receive its motion from another source and so it can provide motion for other things by acting upon them directly. This means that there must be something, which acts without being acted upon in order to provide the first principle of all motion in the universe as a whole.

Plato’s concept of the Craftsman as the creator of the physical world introduces a fascinating perspective on the origins of our reality. By characterizing the Craftsman as a manual laborer, he highlights the deliberate craftsmanship involved in the shaping of the world.

Plato’s Craftsman invites us to contemplate the intricate relationship between the creator and the created, encouraging us to explore the boundaries between the natural and the artificial.

This idea challenges traditional beliefs and invites us to reconsider our understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Aug 5, 2023 | History of the Brotherhood, Illuminati, Philosophy

In the annals of Ancient History, as it relates to the origins of Western Philosophy, Esotericism, and Secret Societies, one man stands at the forefront as being one of the founders. That man was Epimenides of Knossos from the island of Crete who lived in approximately the 7th or 6th century BCE.

For hundreds of years, Epimenides was one of the most famous ancient philosophers predating the great giants of Western philosophy such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, all of whom drew inspiration from his writings. (1) Throughout history, his stories and teachings have been passed down to us by some of the greatest philosophers who have ever lived, leaving an indelible mark on the culture and philosophy of ancient Greece and the whole Western world.

Over the course of many generations, Epimenides was immortalized within Greek history with his extraordinary intellectual and mythical god-like status, thereby elevating him to a divine-like status. As a result, his life and works have captivated the imagination of scholars and storytellers for thousands of years.

In this essay, I aim to shed light on the origins of our Western esoteric traditions, drawing from the perspectives of ancient philosophers and historians. According to some of these most esteemed thinkers, the roots of this tradition can be traced back to Epimenides and the enigmatic Orphic mysteries, originating in the land of Crete and Greece.

Both the Orphic and teachings of Epimenides can be found in the philosophies of some of the world’s greatest philosophers such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle and their intellectual successors such as the Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists who followed this tradition forming a direct lineage from Orpheus. (2) In examining their own sources for their philosophies, they all claim that both Orpheus and Epemenides had equally influenced their own ideas.

According to these accounts, both Orpheus and Epemenides lived at approximately the same time and in the same places with very similar accomplishments. For example, as Orpheus and Epemenides had accomplished, we find that they are similarly immortalized in myth and history for their efforts to revolutionize the secret mysteries in order to create a new state religion and also cleanse the land from a devastating plague.

According to Plato, Epimenides undertook the work assigned to him by the Delphic Oracle, which held a significant influence on the advancement of Hellenic society. (3) Aristotle said that he gave his oracles not about the future, but about things in the past that were obscure.

In myth and history, their influence on both ancient political and religious doctrines has served as the very foundation for shaping the course of Western philosophy and esotericism. Initial concepts that we find deeply intertwined within the philosophical and religious ideas of the collective imagination of many of the early Cretan and Greek philosophers, which became the very cornerstone of Western Esotericism, Philosophy, Gnosticism, and the later Abrahamic religions.

At the center of these ideas was the home of Epimenides and his ancestors, the island of Crete.

Two books Epimenides was said to have written that were mentioned by several eminent ancient authors were The History of Crete and Kretika or Cretika. The “History of Crete” is a comprehensive account of the origins, development, and notable events of the island of Crete.

Epimenides traces the history of the island from its mythical beginnings to the time of his own writing. The work is said to provide valuable insights into Cretan civilization, its social structures, religious practices, and the interplay of various cultural influences. Although the original text of the “History of Crete” has been lost, and our knowledge of its contents comes primarily from references and quotations found in later works by other authors.

“Kretika or Cretika,” on the other hand, is a collection of religious and moral teaching in the form of poems and hymns celebrating the glory and virtues of Crete. These poems praised the island’s natural beauty, its people’s achievements, and the valor of Cretan warriors.

Epimenides wrote;

“There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair land and a rich, begirt with water, and therein are many men innumerable, and ninety cities. And all have not the same speech, but there is confusion of tongues; there dwell Achaeans and there too Cretans of Crete, high of heart, and Cydonians there and Dorians of waving plumes and goodly Pelasgians.”

The “Kretika” served as a means to promote a deep understanding of religious beliefs and practices prevalent in ancient Crete. However, like the “History of Crete,” the original text of “Kretika” has not survived, and our knowledge of its contents is based on fragments and references in other ancient texts.

Diodorus Siculus, the first-century-BC historian of ancient Greece said that he relied upon Epimenides’ work for his Bibliotheca historica claiming that, “I have followed the most trustworthy authorities on Cretan affairs, Epimenides the Theologian, Dosiades, Sosicrates and Laosthenes.” (4)

Both Aristotle and Plutarch included Epimenides in the esteemed group known as the Seven Wise Men according to ancient tradition. The Seven Wise Men hold a significant position in the early stages of Hellenic history, as they played a pivotal role in shaping and consolidating Hellenism.

Plutarch wrote;

“Under these circumstances, they summoned to their aid from Crete Epimenides of Phaestus, who is reckoned as the seventh Wise Man by some of those who refuse Periander a place in the list. He was reputed to be a man beloved of the gods, and endowed with a mystical and heaven-sent wisdom in religious matters.

Therefore the men of his time said that he was the son of a nymph named Balte, and called him a new Cures. On coming to Athens he made Solon his friend, assisted him in many ways, and paved the way for his legislation.”(5)

What is certain, is that many esteemed authorities, from Plato and Aristotle onward, emphasized the religious, political, and social ramifications resulting from the life and work of Epimenides. Other philosophers, such as Parmenides and Heraclitus, drew upon his ideas to shape their own philosophies.

Parmenides, as discussed in “Metaphysics and Ethics in Epimenides’ Teachings” by A. Turner, adopted Epimenides’ emphasis on the existence of a singular reality, in his case, the concept of Being. Heraclitus, known for his philosophy of change and flux, incorporated Epimenides’ insights into the nature of reality and the paradoxes of existence. (6)

Being counted as a main authority for Siculus and among the Seven Wise Men in the early tradition not only attests to Epimenides’ authority among ancient philosophers of Greece, but also signifies his contribution to the fame and collective memory of the Phoenician and Hellenic people.

Now, let us examine these esoteric connections.

EPIMENIDES, PLATO, SAINT PAUL, AND CRETAN LIARS

Perhaps Epimenides is most often remembered for his famous quote known as the “Liar Paradox,” which challenges the very foundations of truth and logic. The quote is from his book called Cretica (Κρητικά) when Minos addresses the god, Zeus.

We find this verse initially appearing in Callimachus'(270 B.C.) Hymn to Jupiter/Zeus (verses 8-11):

“They say that thou, O Zeus, wast born in [Cretan] Ida’s mountains, and that thou wast born in Arcadia. Which, O Father, spoke falsely? The Cretans are always liars: and this we know, for thy tomb, O King, the Cretans fashioned; but thou didst not die, for thou existest always.”

Epimenides’ paradox is mentioned by Epimenides himself, as recorded by Diogenes Laertius in “Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers” (3rd century CE). However, it is important to note that the attribution of the paradox to Epimenides is not certain, and it could have been later attributed to him. (7)

And later, during the Christian era, the apostle Paul references Epimenides’ paradox in the New Testament, specifically in the “Epistle to Titus” (Titus 1:12). Paul says about the Cretans’ reputation;

“One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, The Cretans are always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies” (kata thêria, gasteres argai),” which is an allusion to the paradox.

This connection to Paul, Crete, and the Bible shows Epimenides actively influenced and possibly participated in these Gnostic movements. As I explained, he also influenced many of the early Greek philosophers and historians such as Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, and Diodorus Siclus, to name a few.

We also find the Epimenides’ Paradox in a discussion on liars in “Sophist” by Plato (4th century BCE). In Section 231, Plato mentions Epimenides as an example of a liar who paradoxically claims that all Cretans are liars. Although this particular quote doesn’t directly reference Epimenides’ statement, it engages with the idea of the paradox.

Plato wrote; “The Cretans, according to our account, have not only invented the story of the birth of Zeus, but they have also, as Epimenides says, declared all men to be liars.” (8)

Plato’s student and predecessor, Aristotle also mentions the same quote in his “Metaphysics;”

“But a man may ask whether what is said should be regarded as universally false or only as not universally true; for if what Epimenides says is true, it is false, and if false, it is true.” (9)

Moreover, the island of Crete held a significant place in the hearts of Cretans and Greeks alike, for it was venerated as the very cradle of Greek myths and religion. In particular, it was considered the sacred birthplace of Zeus, the revered father of gods and men.

PYTHAGORAS AND EPIMENIDES:

Pythagoras, the renowned mathematician and philosopher, is said to have encountered Epimenides during his travels to Crete. We are told that he was a student of Epimmenides. It is also well known that Pythagoras has played a pivotal role in the history of Western esotericism expanding upon the philosophical and mathematical doctrine with his followers, the Pythagoreans.

Pythagoras was spoken of and written about much more often. His great fame had the twin effects of making his name the focus of legends, which multiplied over the centuries, and of preserving the memory of the historical events of his time.

Although Epimenides was not directly associated with the Pythagorean school, several Pythagorean fragments and testimonies mention a connection between Pythagoras and Epimenides. These fragments, collected by various ancient authors, provide indirect evidence of Epimenides’ influence on Pythagoras and his followers.

The primary sources on Pythagoras, such as the works of Diogenes Laërtius, Iamblichus, and Porphyry, mention Pythagoras’ journey to Crete. Additionally, Plato’s dialogue “Phaedrus” depicts Socrates discussing the potential influence of Pythagorean thought, suggesting a connection between Pythagoras and Cretan philosophy. (10)

It is important to note that the primary source for this account is Diogenes Laertius’ book on Pythagoras. Laërtius, a doxographer who lived around 200 to 250 C.E., played a crucial role in preserving the biographies of ancient Greek philosophers through his notable work, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. The book consists of ten books that provide a wealth of information from the lives of nearly one hundred philosophers, including Pythagoras and 45 significant figures spanning from the seventh century C.C to the late second century C.E. (11)

A majority of Laërtius’ biographies name the teacher and student of each philosopher, and the people with whom they had personal encounters. To construct this comprehensive account, Laërtius drew information from numerous earlier works, many of which have been lost over time.

According to Laertius, Pythagoras embarked on extensive travels throughout the known world during his quest for knowledge with the intention of acquiring important initiations from various sources. As part of his journey, Pythagoras made a significant stop in Crete to meet Epimenides, a renowned figure of esoteric knowledge.

Epimenides possessed such valuable esoteric wisdom that Pythagoras himself sought initiation from him. Their meeting in Crete was a pivotal moment, as Pythagoras aspired to complete his initiation under Epimenides’ guidance. Together, they ventured into the renowned “Idaeon andron,” a cave of great significance. This cave was believed to be the birthplace of Zeus, the highest deity in Greek mythology.

Many biographical traditions recount Pythagoras’initiation into the mysteries in the Idean Cave on Mount Ida on Crete along with his journeys to culturally advanced eastern countries like Egypt and Babylon, as well as to Italy. This variation in narratives adds an intriguing layer to the understanding of Epimenides’ role and the sacred caves associated with Zeus.

Laertius wrote:

“When he was in Crete with Epimenides, he came down to Idaeon andron

Then (Pythagoras) visited Crete and descended to Idaion Andron accompanied by Epimenides, but also in Egypt to the depths;

but he also visited the shelters of the temples of Egypt. And learned about the gods in secret.”

Porphyry of Tyre , a Neoplatonic philosopher born in Tyre (Roman Phoenicia), mentioned the initiation of Pythagoras on the island of Crete at the cave located at Mount Ida, which was the original home to the Biblical Tribe of Judah (Idumeans, Judeans).

Porphyry wrote in the “Life of Pythagoras;”

“Going to Crete, Pythagoras besought initiation from the priests of Morgos, one of the Idaean Dactyli, by whom he was purified with the meteoritic thunder-stone. In the morning he lay stretched upon his face by the seaside; at night, he lay beside a river, crowned with a black lamb’s woolen wreath.

Descending into the Idaean cave, wrapped in black wool, he stayed there twenty-seven days, according to custom; he sacrificed to Zeus, and saw the throne which there is yearly made for him. On Zeus’s tomb, Pythagoras inscribed an epigram, “Pythagoras to Zeus,” which begins: “Zeus deceased here lies, whom men call Jove.” (11)

The name “Idaean Dactyli” is a reference to Mount Ida. Strabo, a Greek geographer and historian, provides geographical and historical information about Crete in his work “Geography.” Strabo had written, that the priests from Crete called the Curetes (Kuretes), were also known as the Corybantes, Idean Dactyls, Cabiri, and Telchines; which are all names that were used interchangeably with one another.

There are more mythological connections between Zeus, Mount Ida and the island of Crete. When the infant Zeus was born to his mother Rhea, his vengeful father Cronus had learned from Gaia and Uranus that his own son was destined to overcome him and become King. Rhea knowing what his father would do to him, had devised a plan to hide the real Zeus in a cave on Mount Ida in Crete, and in which she entrusted his care to the priesthood of the Curetes, who were also known as the “Ministers of Cybele.”

Although his writing does not explicitly discuss Epimenides’ influence on other philosophers, it offers contextual information about the time and place in which Epimenides and Pythagoras lived, helping to understand the cultural and intellectual milieu that facilitated philosophical exchanges.(12)

Epimenides’ ideas about paradoxes and the nature of truth deeply influenced Pythagoras’ philosophical pursuits. Pythagoras, known for his fascination with numbers and their mystical properties, was intrigued by Epimenides’ paradox and its implications for understanding the foundations of knowledge and logic.

According to “The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy” by M. Williams, Pythagoras recognized the value of Epimenides’ teachings on religious devotion and the concept of the soul. Epimenides’ belief in the interconnection between the divine and mortal realms resonated deeply with Pythagoras’ own exploration of the harmony and order underlying the universe. (13)

The influence of Epimenides is especially evident in Pythagoras’ theory of the transmigration of souls, where he posited that the soul is immortal and can undergo successive reincarnations.

One notable concept that Pythagoras adopted from Epimenides was the notion of purification of the soul. Epimenides taught that the soul could be cleansed through spiritual practices and rituals, leading to a harmonious existence. Pythagoras embraced this idea, incorporating it into his theory of the transmigration of souls and the pursuit of moral and intellectual virtues leading to reason.

This concept can be found in the Abrahamic religions like in Christianity with saving your soul or being born again. Not everyone who emarks on the wrong path or lives ignorantly, immorally, and unethical is damned to a life of misery.

It is believed that Pythagoras incorporated elements of Epimenides’ paradoxes into his own teachings, which emphasized the pursuit of truth and the interconnectedness of all things. Pythagorean philosophy, with its emphasis on harmony, the eternal nature of the soul, and the mathematical underpinnings of the universe, owes a debt to Epimenides’ thought.

PLATO AND EPIMENIDES

Plato, the renowned philosopher and student of Socrates, was also influenced by Epimenides. Although there is limited direct evidence of their interaction, Plato’s works reflect Epimenides’ influence through shared philosophical themes and ideas. Epimenides’ belief in the existence of divine forces, the significance of myth and symbolism, and the pursuit of higher truths resonated strongly with Plato’s philosophical inquiries.

In Book 10 of “Laws, Plato’s portrayal of Epimenides in “Laws” draws heavily from the mythological traditions of ancient Greece to discuss the nature of divine law, prophecy, and the moral foundations of society. He presents Epimenides as a wise and virtuous individual who possesses an understanding of divine order and the significance of rituals and sacrifices. (14)

Plato describes Epimenides as a seer, someone who has a deep connection to the divine and the supernatural. Epimenides’ character serves as an authority on religious rituals and the interpretation of signs from the gods. He argues that these rituals are crucial for maintaining social cohesion and order.

One of Epimenides’ most famous contributions, the paradox of the “Cretan Liar,” had a lasting impact on Plato’s philosophical discourse. The paradox posed the question of whether a statement made by a Cretan asserting that all Cretans were liars could be true. This paradox challenged notions of truth, language, and self-reference, inspiring Plato’s exploration of these concepts in his dialogues.

Epimenides’ ideas on the existence of an ultimate reality beyond the sensory realm deeply influenced Plato’s theory of Forms or Ideas. Plato incorporated the notion of an eternal and unchanging realm of perfect forms, which closely aligned with Epimenides’ emphasis on the transcendental nature of truth. Additionally, Epimenides’ teachings on the significance of morality and the pursuit of virtue influenced Plato’s ethical philosophy, particularly his concept of the philosopher-king and the ideal city-state.

Plato mentions Epimenides in his Laws in the discussion between Megillus and Clinias in which Clinias claims a family connection to the Cretan prophet:

CLINIAS: My story, too, Stranger, when you hear it, will show you that you may boldly say all you wish. You have probably heard how that inspired man Epimenides, who was a family connection of ours, was born in Crete; and how ten years before the Persian War, in obedience to the oracle of the god, he went to Athens and offered certain sacrifices which the god had ordained; and how, moreover, when the Athenians were alarmed at the Persians’ expeditionary force, [642e] he made this prophecy —

“They will not come for ten years, and when they do come, they will return back again with all their hopes frustrated, and after suffering more woes than they inflict.” Then our forefathers became guest-friends of yours, and ever since both my fathers and I myself.

MYTHS AND LEGENDS

One notable aspect of Epimenides’ reputation among the Cretans was their belief in his divine origins. His mythical lineage can be traced back to the legendary King Minos, famous for his labyrinth and the Minotaur.

From a young age, he was said to have exhibited exceptional intelligence and exhibited a deep connection with nature, spending hours wandering the hills and caves surrounding his home. It was during one of these excursions that he encountered an enigmatic figure, a god-like presence who granted him an extraordinary gift.

Epimenides’ reputation as a sage grew exponentially when he ventured into the famed Labyrinth of Knossos, seeking answers to the mysteries of existence. Legend has it that he spent days wandering through its winding corridors, encountering mythical creatures and unraveling the secrets hidden within. Some accounts even suggest that he communed with the Minotaur, transforming it from a fearsome monster into a docile creature.

There is a famous legend surrounding the origination of the prophetic talents of Epimenides which the Greeks had usually embellished in mythology. The legend is, that while Epimenides was tending his father’s sheep, he is said to have fallen asleep for 40 or 57 years (on Mount Ida on the island of Crete) in a cave sacred to the King of Gods and Men, Zeus, and after which he reportedly awoke with the gift of prophecy.

The story appears to be an allegory, showing us that Epimenides was asleep “figuratively” until he reached his older years when he became enlightened.

At this moment, he finally awoke from his metaphorical slumber within the cave and attained inner enlightenment or Gnosis, becoming exceptionally wise in various disciplines and attaining a godlike status. This very cave gained worldwide renown as it appears to have served as an exclusive venue for initiation into the Orphic ceremonies and secret mysteries.

According to the accounts of the ancient historian, Theopompus, Epimeminides was said to have been divinely inspired to construct a sacred shrine dedicated to Zeus. He refers to the Creatn Prophets as the new Kouros or Koures, who had a significant connection to Zeus Cretagenes, possibly serving as his attendant or priest.

Though the precise nature of their association remains somewhat speculative, it is plausible that Epimenides served as an attendant or priest, carrying out sacred rites and rituals on behalf of the god. His actions and well-documented history exemplify his role as a defender and follower of Zeus, and also as one of the founders of the mystery schools, which left an immortal mark on the religious landscape of ancient Crete and the Ancient philosophers of Greece.

In Greek mythology, Jupiter was equated with Zeus, the king of the gods. The planet Jupiter has been associated with various names in different mythologies throughout history. The Romans also identified the planet with their supreme deity, giving him the same name. These associations can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and Romans who observed the planet and attributed its characteristics to their respective gods.

Plutarch refers to him as the “New Kouretes,” and the Cretans regarded his mother as the nymph Balte (Βάλτη) [2]. The divine connection attributed to Epimenides reflects the high regard in which he was held by his fellow Cretans.

Plutarch mentions both Epimenides and Solon were in Athens at the same time, and on friendly terms. The purification of Athens by Epimenides is generally assigned to B.c. 596 — 595, shortly before the archonship of Solon in 594. (15)

Epimenides assisted with the proper methods for the regulation of the Athenian Commonwealth to restore law and order. His expertise in sacrifices and the reform of funeral practices greatly assisted Solon in his efforts to reform the Athenian state.

Plutarch also said that Epimenides was almost like a messiah to the Greeks at the time because he had purified Athens and that the only reward he would accept was a branch of the sacred olive, and a promise of perpetual friendship between Athens and Knossos.

Plutarch wrote;

“Epimenides purified Athens after the pollution brought by the Alcmeonidae, and that the seer’s expertise in sacrifices and reform of funeral practices were of great help to Solon in his reform of the Athenian state. The only reward he would accept was a branch of the sacred olive, and a promise of perpetual friendship between Athens and Knossos.”

Maximus of Tyre confirms this event in the 2nd century CE;

“There came to Athens also another Cretan named Epimenides. He was marvelously skilled in the things of God, so that he saved the city of the Athenians when it was perishing through pestilence and sedition; and he was skillful in these matters, not because he had learned them, but, as he related, long sleep and a dream had been his inspiration … he had come into relations with the gods and the oracles of the gods and Truth and Justice.

For Solon had proclaimed at the time;

“In the day of vengeance, dark Earth, mightiest mother of the gods of Olympus, will be my surest witness of this, Solon’s account from whom I removed pillars planted in many places, and whom I freed from her bonds. Many citizens, who had been sold into slavery under the law or against it, I brought back to Athens their home; some of them spoke Attic no longer, their speech being changed in their many wanderings. Others who had learnt the habits of slaves at home, and trembled before a master, I made to be free men.

All this I accomplished by authority, uniting force with justice, and I fulfilled my promise.” (16)

Epimenides was said to have founded numerous religious organizations and installed statues of the gods throughout the streets of Athens. His intention was to instill in the minds of Athenians the constant presence of divine nature in various forms, where no indecency is allowed and everything must be regarded as sacred and untainted.

The ultimate goal and outcome were the thorough purification of the city and the establishment of virtuous guidelines for communal existence. It was imperative for the citizens to dwell in the ever-present aura of the divine.

Pausanias reports, that when Epimenides died, his skin was found to be covered with tattoo writing. Some modern scholars have seen this as evidence, that Epimenides was heir to the shamanic religions of Central Asia, because tattooing is often associated with shamanic initiation.”

He also places Epimenides at Knossos and claims he was killed and buried near the statue of Athena. Pausinias wrote:

“By the Canopy is a circular building [in Sparta], and in it images of Zeus and Aphrodite surnamed Olympioi. This, they say, was set up by Epimenides, but their account of him does not agree with that of the Argives, for the Lakedaimonians deny that they ever fought with the Knossians.”

[2.21.3] A sanctuary of Athena Trumpet they say was founded by Hegeleos. This Hegeleos, according to the story, was the son of Tyrsenus, and Tyrsenus was the son of Heracles and the Lydian woman; Tyrsenus invented the trumpet, and Hegeleos, the son of Tyrsenus, taught the Dorians with Temenus how to play the instrument, and for this reason gave Athena the surname Trumpet.

Before the temple of Athena is, they say, the grave of Epimenides. The Argive story is that the Lacedaemonians made war upon the Cnossians and took Epimenides alive; they then put him to death for not prophesying good luck to them, and the Argives taking his body buried it here.”

CONCLUSION:

Epimenides of Crete, with his paradoxes and philosophical ideas, left an enduring legacy on the development of Western philosophy. Through his influence on Socrates, Pythagoras, Plato, and other great philosophers, Epimenides’ exploration of truth, language, and metaphysics contributed to both the foundation and evolution of philosophical thought.

As an intermediary between the earthly and divine realms, Epimenides’ influence reached far beyond the confines of his immediate surroundings. His reputation as a philosopher, religious leader, and visionary extended throughout Greece and into Italy, capturing the attention and admiration of people from various parts of the world.

As we delve into the works of these philosophers and examine their ideas, we can trace the threads of Epimenides’ influence, highlighting the lasting impact of his contributions on philosophical discourse throughout the ages. Although direct references to Epimenides may be scarce, the parallels between their ideas, as found in primary sources such as Diogenes Laertius, Plato’s dialogues, and Aristotle’s works, suggest a deep and lasting influence.

Additionally, Pythagorean fragments, testimonies, and anecdotes collected by authors like Aelian offer indirect evidence of the connection between Epimenides and Pythagoras. While the exact extent of Epimenides’ influence may remain a matter of speculation, the interplay of their philosophical ideas demonstrates the rich and interconnected philosophical themes and concepts in their works highlighting the lasting influence on Western Esotericism.

Epimenides’ role in shaping the metaphysical and spiritual landscape of the time was widely acknowledged and respected. His presence and influence epitomized the deep connection between the mortal and divine realms, leaving an indelible mark on the religious consciousness of the ancient world that lasts until this very day.

I believe that the immortal story of Epimenides enshrined as the mythical Orpheus proves the origins of our Western religious and esoteric traditions. An ancient custom that is also connected to the sacred history of the island of Crete, solidifying its status as a spiritual epicenter for the various Gnostic and philosophical schools that came after throughout history.

SOURCES:

1. Guthrie, W.K.C. “A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans.” Cambridge University Press, 1962.

2. Forsyth, Neil. “Epimenides of Knossos.” In “The Oxford Classical Dictionary,” edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, 4th ed., 525-526. Oxford University Press, 2012

3. PLATO LAWS – § 642

4. Diodorus Siculus, “Library of History,” Book 5.77-78.

5. Plutarch, “Life of Solon,” in Plutarch’s Lives, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914

6. Metaphysics and Ethics in Epimenides’ Teachings” by A. Turner

6. Guthrie, W. K. C. (1980). “A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans.

7. Laërtius, Diogenes. “Lives of Eminent Philosophers.” Translated by R. D. Hicks, Harvard University Press, 1925

8. Plato, “Phaedrus,” 260d

9. Aristotle, “Metaphysics,” Book 4, Part 7

10. Life of Pythagoras (1920). English translation

9. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924), 10.4.14

10. The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy by M. Williams

11. Laërtius, Diogenes. “Lives of Eminent Philosophers.” Translated by R. D. Hicks, Harvard University Press, 1925

12. Strabo, “Geography,” in The Geography of Strabo, trans. Horace Leonard Jones

13. The Influence of Epimenides on Pythagorean Philosophy” by M. Williams

14. Plato. “Laws.” Translated by Trevor J. Saunders, Penguin Classics, 1970

15. Plutarch, Life of Solon, 12; Aristotle, Ath. Pol. 1

16. Asianic Elements in Greek Civilisation: The Gifford Lectures in the University of Edinburgh – Chapter 3 1915-16: Sir Ramsay

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.

by Moe | Jul 8, 2023 | Freemasonry, Gnosis, Illuminati, Philosophy

The ancient Greek world was a rich tapestry of religious and philosophical ideas, with diverse cults and mystery traditions offering individuals different pathways to a deeper understanding of the divine and the self.

Among these, the Orphic Mysteries emerged in approximately the 6th Century BC as a prominent philosophical movement, characterized by its unique mythology, rituals, and esoteric teachings. (1)

Rooted in the mythological and ritualistic traditions of the Orphic movement, these mysteries offered a path to spiritual enlightenment and liberation. Numerous sources contribute to our understanding of Orpheus and his significance in Greek mythology.

Throughout history, numerous renowned philosophers and historians, spanning several centuries, have asserted that Orpheus existed as an actual human being, elevating him to a god-like status. His life story is recounted in various Greek myths, weaving together elements of music, heroism, and supernatural abilities.

According to these accounts, his accomplishments revolved around his efforts to revolutionize the state religion and cleanse the land from a devastating plague.

The Orphic teachings can be found in the philosophies of renowned thinkers such as Pythagóras, Socrates (Sôkrátîs), Plato (Plátôn), and their intellectual successors such as the Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists who followed in this tradition forming a direct lineage from Orpheus. (2) His political and religious doctrines served as the foundation for shaping the course of Western philosophy as a whole.

As the 19th century historian and expert Thomas Taylor wrote;

“For all the Grecian theology is the progeny of the mystic tradition of Orpheus; Pythagoras first of all learning from Aglaophemus the orgies of the Gods, but Plato in the second place receiving an all-perfect science of the divinities from the Pythagoric and Orphic writings.” (3)

The various cults surrounding the teachings of Orpheus are prominently featured in these ancient texts, solidifying his status as a significant figure in the mythological pantheon. He is credited as being the founder of the theology of the Greeks such as Eleusisian mysteries and the Mysteries of Dionysos.

According to historical accounts, it is believed that the ancient Greek Mystery Cults established by Orpheus at Eleusis were heavily influenced by Egyptian traditions, which were transmitted through Ancient Phoenicia, the island of Crete, and Greece.

Diodorus Siculus, the 2nd century Greek historian, who is best known for his monumental work on universal history of the world, “Bibliotheca Historica” (Library of History), said that he relied on the work of Orpheus as one of his main sources.

Siculus claimed that he was held in such high esteem because he was the most knowledgeable man of the time who was honored by both the Greeks and the Egyptians. He also mentions that the rituals associated with Osiris, an Egyptian god, were remarkably similar to those of Dionysus, who was said to be a priest of Orpheus.

Siculus wrote:

“In After-times, Orpheus, by reason of his excellent Art and Skill in Musick, and his Knowledge in Theology, and Institution of Sacred Rites and Sacrifices to the Gods, was greatly esteemed among the Grecians, and especially was received and entertained by the Thebans, and by them highly honored above all others; who being excellently learned in the Egyptian Theology, brought down the Birth of the ancient Osiris, to a far later time and to gratify the Cadmeans or Thebans, instituted new Rites and Ceremonies, at which he ordered that it should be declared to all that were admitted to those Mysteries, that Dionysus or Osiris was begotten of Semele by Jupiter.

The People therefore partly through Ignorance, and partly by being deceived by the dazzling Luster of Orpheus his Reputation, and with their good Opinion of his Truth and Faithfulness in this matter (especially to have this God reputed a Grecian, being a thing that humored them) began to use these Rites, as is before declared. And with these Stories the Mythologists and Poets have filled all the Theaters, and now it’s generally received as a Truth, not in the least to be questioned.” (4)

The 20th-century historian and author, Otto Kern said in his Orphicorum Fragmenta that this testimony, from Diodorus of Sicily, says that Orpheus took his mystic rites from Egypt and that the Egyptian rite of Osiris is the same as that of Dionysus, the name alone being changed.

The parallels between the Egyptian and Greek mysteries extended beyond Dionysus and Osiris. Diodorus also noted that the Eleusinian mysteries shared similarities with the rites of Isis and Demeter.

“Orpheus, for instance, brought from Egypt most of his mystic ceremonies, the orgiastic rites that accompanied his wanderings, and his fabulous account of his experiences in Hades. For the rite of Osiris is the same as that of Dionysus, and that of Isis very similar to that of Demeter, the names alone having been interchanged; and the punishments in Hades of the unrighteous the Fields of the Righteous, and the fantastic conceptions, current among the many, which are figments of the imagination, all these were introduced by Orpheus in imitation of Egyptian funeral customs.” (5)

This further supports the notion that there was an intermingling of religious practices and beliefs between these ancient cultures of Greece and Egypt.

According to Pausanias, a Greek historian from the second century, individuals seeking knowledge (gnosis) and spiritual enlightenment would become initiates of the Mystery Schools established by Orpheus. These schools were dedicated to teaching ceremonial magic, unraveling the mysteries of the divine realms, and imparting the wisdom of herbal remedies for healing and warding off divine wrath.

Pausanias noted that both men and women flocked to these schools in great numbers, desiring purification and forgiveness for their unholy actions, so that they could lead virtuous lives that pleased the gods and gained their favor. (6)

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), one of the world’s most prominent Swiss psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, acknowledged the significance of Orphism on the world’s religions and cultures. Jung wrote that Ophism “inspired the religious ruminations and philosophic speculation of many centuries” and it offered “initiation into the secrets of the earth,” suggesting a deep connection with the mysteries of the natural world. (7)

For example, one of the central aspects of the Orpheus myth is his descent into the Underworld to retrieve his deceased wife, Eurydice. This journey is laden with symbolism and mirrors the hero’s journey archetype, which Jung believed was a recurring pattern in myths and religious tales worldwide.

Unlike the rites of Osiris and Isis, which primarily involved lamentations for the deaths of the deities associated with agriculture and vegetation, the Orphic Mysteries focused on the spiritual enlightenment of the initiate. (8)

Jung viewed Orphism as an attempt to reconcile the opposites within the individual psyche. He saw it as a profound expression of the human psyche’s desire for transcendence and spiritual liberation. He believed that Orphism represented a collective striving for connection with the divine, reflecting the innate human longing for a deeper understanding of the self and the cosmos.

In his book “Psychology and Alchemy,” he stated, “Orphism was a psychology of religion with a strong Gnostic coloring, representing the sum total of philosophical and religious endeavors to explain life as a meaningful whole.” Jung recognized the Orphic tradition as a quest for unity and wholeness, aiming to bridge the gap between conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. (9)

In “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious” (1934-1954), Jung discussed the hero’s journey as a transformative process of self-discovery, representing the individual’s confrontation with the unconscious and the integration of its contents. Orpheus’ descent into the Underworld signifies a quest for personal growth and spiritual development, echoing the individuation process in Jungian psychology. (10)

THE ORPHIC CONNECTION TO FREEMASONRY

This philosophical lineage and connection to the ancient mystery schools of Greece and Crete also continues on to today through the teachings of Gnosticism, religion, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and the Illuminati. Many of our most prominent scholars have acknowledged Orphic influences on our Western Esoteric mystery traditions.

One of the oldest connections is to Pythagoras, who lived in the 6th century BC. He was a Greek philosopher, mathematician and spiritual leader. He founded the philosophical and religious school of Pythagoreanism. Pythagoras’ teachings were also transmitted to the Western world through prominent medieval alchemists and subsequent practitioners of magic and secret societies, including the fraternities of Freemasonry and the Illuminati, in which Pythagoras played a central role.

This influence can be attributed to the origins of the Western mystery traditions along with their syncretic nature, where ideas, symbols, and religious customs have migrated from Egypt to Crete and Greece to the rest of the Western world, while sharing many of the same customs and rituals between different societies and cultures. These migrations of people which include language, history, religion, and Freemasonry can be traced throughout history to their true origins.

According to the Italian philosopher, scholar, and current Grand Master of the Academy of the Illuminati, Giuliano Di Bernardo;

“Orphism has had a considerable influence on the nascent philosophy not so much over the doctrine of reincarnation as for the dualistic conception of man. For the first time, man is understood as personifying two opposed principles: the immortal soul and the mortal body. This gives rise to a dualism that will cross the entire span of the history of philosophical thought up to our own days. Without Orphism, we would be unable to explain Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and all the philosophers who draw upon them.”

Di Bernardo further stated;

“As far as the initiatory foundation is concerned, between the Freemasonry and the Order of the Illuminati there are no differences: they are both heirs of the ancient Orphic and Pythagorean mysteries. The differences when compared to the present practices can pertain to the symbols, the rituals and the ceremonies.” (11)

Therefor, students of Western Esotericism and true symbolic Masonry should have a firm understanding of Orphic history. Famous Freemason and scholar Albert Pike, in his seminal work “Morals and Dogma,” suggests a Masonic connection to the Orphic Mysteries. Pike wrote;

“The distinction between the esoteric and exoteric doctrines (a distinction purely Masonic), was always and from the very earliest times preserved among the Greeks. It remounted to the fabulous times of Orpheus; and the mysteries of Theosophy were found in all their traditions and myths. And after the time of Alexander, they resorted for instruction, dogmas, and mysteries, to all the schools, to those of Egypt and Asia, as well as those of Ancient Thrace, Sicily, Etruria, and Attica.” (12)

The renown 20th century Masonic philosopher and historian, 33rd Degree Freemason, Many. P. Hall said:

“According to Iamblichus and Proclus, the Grecian theology was derived from the teachings of Orpheus. From Orpheus the doctrine descended to Pythagoras, and from Pythagoras to Plato. These three men together were the founders and disseminators of the Secret Doctrine which had been brought from Asia in the second millennium B. C.

In the words of Proclus, “What Orpheus delivered mystically through arcane narrations, this Pythagoras learned when he celebrated orgies in

the Thracian Libethra, being initiated by Aglaophemus in the mystic wisdom which Orpheus derived from his mother Calliope, in the mountain Pangaeus.” (13)

The influence of Orphic ideas within Freemasonry can be seen when examining Freemasonry from both a philosophical and symbolic perspective. One of the key aspects that highlights this symbolic connection between the Orphic Phanes, Plato’s Demiurgic Craftsman, and the Masonic Grand Architect of the Universe becomes readily apparent.

Both the Orphic mysteries and Freemasonry advocate for moral conduct, personal transformation, and the pursuit of divine knowledge. While the specific doctrines and practices may differ, the underlying principles of virtue, integrity, self-improvement, and enlightenment connect these traditions across time.

According to Dr. Nicolas Laos the Grand Master of the Autonomous Order of the Modern and Perfecting Rite of Symbolic Masonry (A∴O∴M∴P∴R∴S∴M∴), the beginning of Western esotericism, along with the Freemasons and the Illuminati originates with the ancient Orphic mysteries:

“Adam Weishaupt founded the Order of the Illuminati on 1 May 1776 in Bavaria.

Its declared purpose was to bring its members to the highest degree of morality and virtue, to free their minds from prejudice and superstition, and to reform the world by defeating the evils that afflict it.