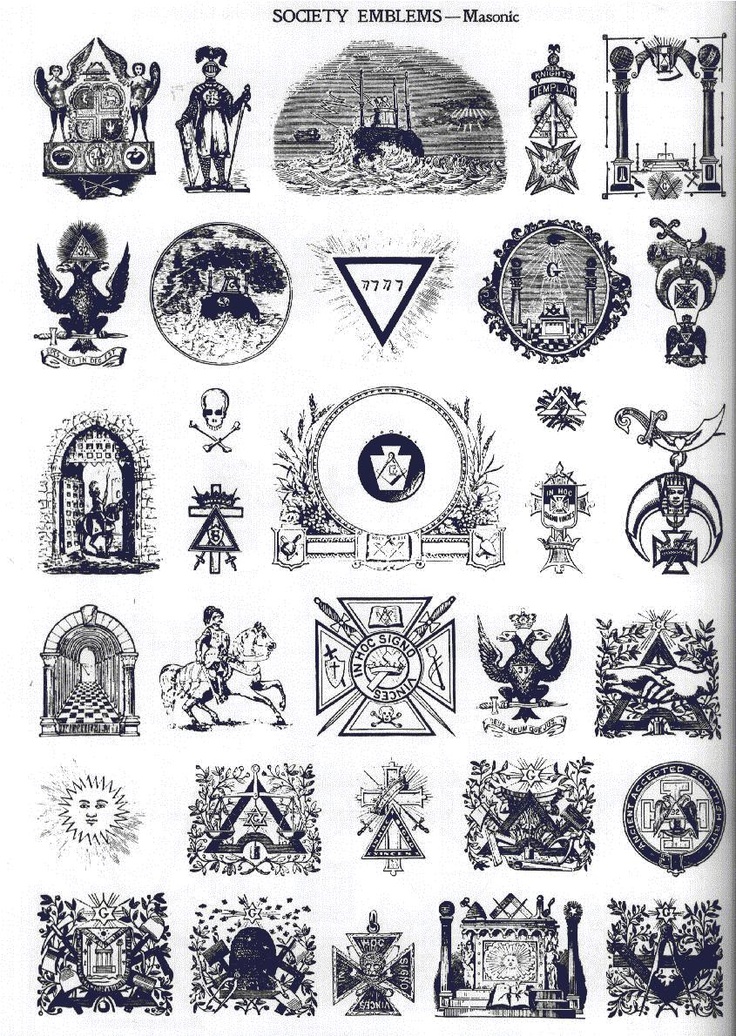

The Popol Vuh was discovered by Father Ximinez in the seventeenth century. It was translated into French by Brasseur de Bourbourg and published in 1861. The only complete English translation is that by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, which ran through the early files of The Word magazine and which is used as the basis of this article. A portion of the Popol Vuh was translated into English, with extremely valuable commentaries, by James Morgan Pryse, but unfortunately his translation was never completed. The second book of the Popol Vuh is largely devoted to the initiatory rituals of the Quiché nation. These ceremonials are of first importance to students of Masonic symbolism and mystical philosophy, since they establish beyond doubt the existence of ancient and divinely instituted Mystery schools on the American Continent.

Lewis Spence, in describing the Popol Vuh, gives a number of translations of the title of the manuscript itself. Passing over the renditions, “The Book of the Mat” and “The Record of the Community,” he considers it likely that the correct title is “The Collection of Written Leaves,” Popol signifying the “prepared bark” and Vuh, “paper” or “book” from the verb uoch, to write. Dr. Guthrie interprets the words Popol Vuh to mean “The Senate Book,” or “The Book of the Holy Assembly”; Brasseur de Bourbourg calls it “The Sacred Book”; and Father Ximinez designates the volume “The National Book.” In his articles on the Popol Vuh appearing in the fifteenth volume of Lucifer, James Morgan Pryse, approaching the subject from the standpoint of the mystic, calls this work “The Book of the Azure Veil.” In the Popol Vuh itself the ancient records from which the Christianized Indian who compiled it derived his material are referred to as “The Tale of Human Existence in the Land of Shadows, and, How Man Saw Light and Life.”

The meager available native records contain abundant evidence that the later civilizations of Central and South America were hopelessly dominated by the black arts of their priestcrafts. In the convexities of their magnetized mirrors the Indian sorcerers captured the intelligences of elemental beings and, gazing into the depths of these abominable devices, eventually made the scepter subservient to the wand. Robed in garments of sable hue, the neophytes in their search for truth were led by their sinister guides through the confused passageways of necromancy. By the left-hand path they descended into the somber depths of the infernal world, where they learned to endow stones with the power of speech and to subtly ensnare the minds of men with their chants and fetishes. As typical of the perversion which prevailed, none could achieve to the greater Mysteries until a human being had suffered immolation at his hand and the bleeding heart of the victim had been elevated before the leering face of the stone idol fabricated by a priestcraft the members of which realized more fully than they dared to admit the true nature of the man-made demon. The sanguinary and indescribable rites practiced by many of the Central American Indians may represent remnants of the later Atlantean perversion of the ancient sun Mysteries. According to the secret tradition, it was during the later Atlantean epoch that black magic and sorcery dominated the esoteric schools, resulting in the bloody sacrificial rites and gruesome idolatry which ultimately overthrew the Atlantean empire and even penetrated the Aryan religious world.

THE MYSTERIES OF XIBALBA

The princes of Xibalba (so the Popol Vuh recounts) sent their four owl messengers to Hunhun-ahpu and Vukub-hunhun-ahpu, ordering them to come at once to the place of initiation in the fastnesses of the Guatemalan mountains. Failing in the tests imposed by the princes of Xibalba, the two brothers–according to the ancient custom–paid with their lives for their shortcomings. Hunhun-ahpu and Vukub-hunhun-ahpu were buried together, but the head of Hunhun-ahpu was placed among the branches of the sacred calabash tree which grew in the middle of the road leading to the awful Mysteries of Xibalba. Immediately the calabash tree covered itself with fruit and the head of Hunhun-ahpu “showed itself no more; for it reunited itself with the other fruits of the calabash tree.” Now Xquiq was the virgin daughter of prince Cuchumaquiq. From her father she had learned of the marvelous calabash tree, and desiring to possess some of its fruit, she journeyed alone to the somber place where it grew. When Xquiq put forth her hand to pick the fruit of the tree, some saliva from the mouth of Hunhun-ahpu fell into it and the head spoke to Xquiq, saying: “This saliva and froth is my posterity which I have just given you. Now my head will cease to speak, for it is only the head of a corpse, which has no more flesh.”

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.