“Raymond had apartments assigned him in the Tower, and there he tells us he transmuted fifty thousand pounds weight of quicksilver, lead, and tin into pure gold, which was coined at the mint into six million of nobles, each worth about three pounds sterling at the present day. Some of the pieces said to have been coined out of this gold are still to be found in antiquarian collections. [While desperate attempts have been made to disprove these statements, the evidence is still about equally divided.] To Robert Bruce he sent a little work entitled Of the Art of Transmuting Metals. Dr. Edmund Dickenson relates that when the cloister which Raymond occupied at Westminster was removed, the workmen found some of the powder, with which they enriched themselves.

“During Lully’s residence in England, he became the friend of Roger Bacon. Nothing, of course, could be further from King Edward’s thoughts than to go on a crusade. Raymond’s apartments in the Tower were only an honorable prison; and he soon perceived how matters were. He declared that Edward would meet with nothing but misfortune and misery for his breach of faith. He made his escape from England in 1315, and set off once more to preach to the infidels. He was now a very old man, and none of his friends could ever hope to see his face again.

“He went first to Egypt, then to Jerusalem, and thence to Tunis a third time. There he at last met with the martyrdom he had so often braved. The people fell upon him and stoned him. Some Genoese merchants carried away his body, in which they discerned some feeble signs of life. They carried him on board their vessel; but, though he lingered awhile, he died as they came in sight of Majorca, on the 28th of June, 1315, at the age of eighty-one. He was buried with great honour in his family chapel at St. Ulma, the viceroy and all the principal nobility attending.”

NICHOLAS FLAMMEL

In the latter part of the fourteenth century there lived in Paris one whose business was that of illuminating manuscripts and preparing deeds and documents. To Nicholas Flammel the world is indebted for its knowledge of a most remarkable volume, which he bought for a paltry sum from some bookdealer with whom his profession of scrivener brought him in contact. The story of this curious document, called the Book of Abraham the Jew, is best narrated

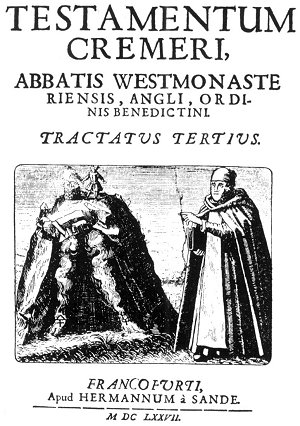

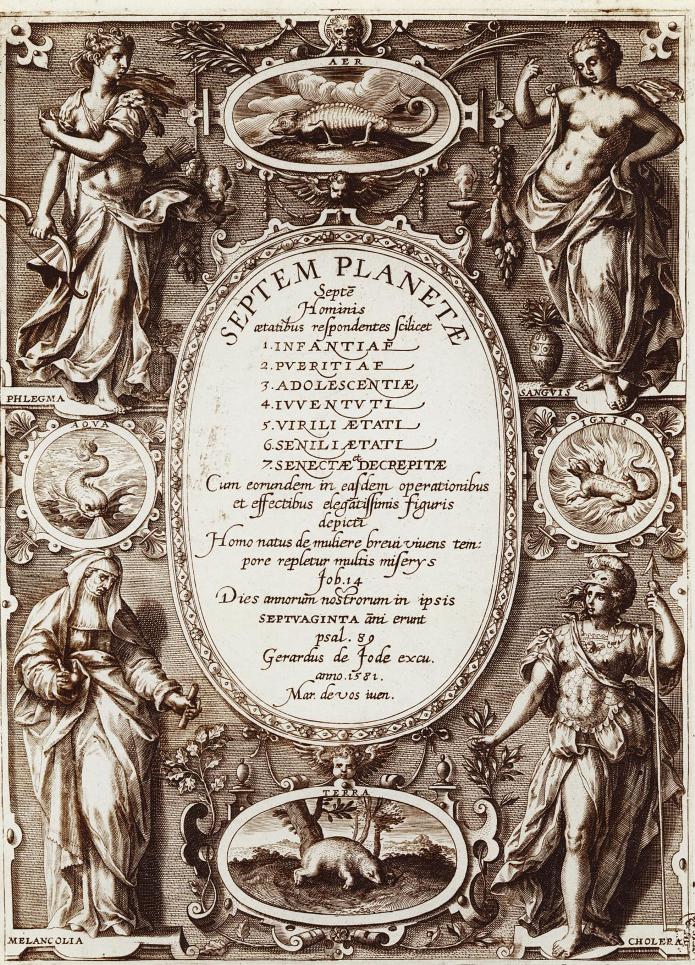

TITLE PAGE OF ALCHEMICAL TRACT ATTRIBUTED TO JOHN CREMER.

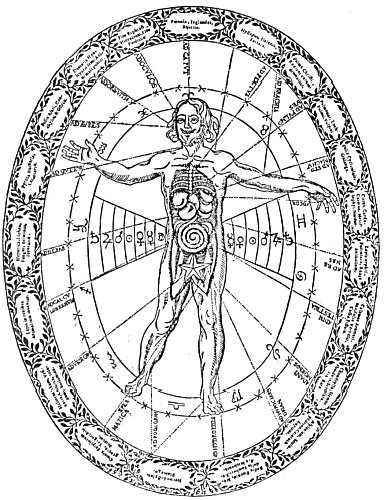

From Musæum Hermeticum Reformatum et Amplificatum. John Cremer, the mythical Abbot of Westminster, is an interesting personality in the alchemical imbroglio of the fourteenth century. As it is not reasonably certain that m abbot by such a name ever occupied the See of Westminster, the question naturally arises, “Who was the person concealing his identity under the Pseudonym of John Cremer?” Fictitious characters such as John Cremer illustrate two important practices of mediæval alchemists: (1) many persons of high political or religious rank were secretly engaged in Hermetic chemical research but, fearing persecution and ridicule, published their findings under various pseudonyms; (2) for thousands of years it was the practice of those initiates who possessed the true key to the great Hermetic arcanum to perpetuate their wisdom by creating imaginary persons, involving them in episodes of contemporaneous history and thus establishing these beings as prominent members of society–in some cases even fabricating complete genealogies to attain that end. The names by which these fictitious characters were known revealed nothing to the uniformed. To the initiated, however, they signified that the personality to which they were assigned had no existence other than a symbolic one. These initiated chroniclers carefully concealed their arcanum in the lives, thoughts, words. and acts ascribed to these imaginary persons and thus safely transmitted through the ages the deepest secrets of occultism as writings which to the unconversant were nothing more than biographies.

p. 152

in his own words as preserved in his Hieroglyphical Figures: “Whilst therefore, I Nicholas Flammel, Notary, after the decease of my parents, got my living at our art of writing, by making inventories, dressing accounts, and summing up the expenses of tutors and pupils, there fell into my hands for the sum of two florins, a guilded book, very old and large. It was not of paper, nor of parchment, as other books be, but was only made of delicate rinds (as it seemed to me) of tender young trees. The cover of it was of brass, well bound, all engraven with letters, or strange figures; and for my part I think they might well be Greek characters, or some such like ancient language. Sure I am. I could not read them, and I know well they were not notes nor letters of the Latin nor of the Gaul, for of them we understand a little.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.