Even in death Paracelsus found no rest. Again and again his bones were dug up and reinterred in another place. The slab of marble over his grave bears the following inscription: “Here lies buried Philip Theophrastus the famous Doctor of Medicine who cured Wounds, Leprosy, Gout, Dropsy and other incurable Maladies of the Body, with wonderful Knowledge and gave his Goods to be divided and distributed to the Poor. In the Year 1541 on the 24th day of September he exchanged Life for Death. To the Living Peace, to the Sepulchred Eternal Rest.”

A. M. Stoddart, in her Life of Paracelsus, gives a remarkable testimonial of the love which the masses had for the great physician. Referring to his tomb, she writes: “To this day the poor pray there. Hohenheim’s memory has ‘blossomed in the dust’ to sainthood, for the poor have canonized him. When cholera threatened Salzburg in 1830, the people made a pilgrimage to his monument and prayed him to avert it from their homes. The dreaded scourge passed away from them and raged in Germany and the rest of Austria.”

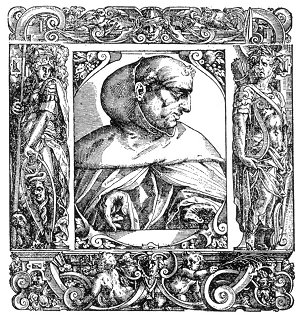

ALBERTUS MAGNUS.

From Jovius’ Vitae Illustrium Virorum. Albert de Groot was born about 1206 and died at the age of 74. It has been said of him that he was “magnus in magia, major in philosophia, maximus in theologia.” He was a member of the Dominican order and the mentor of St. Thomas Aquinas in alchemy and philosophy. Among other positions of dignity occupied by Albertus Magnus was that of Bishop of Regensburg. He was beatified in 1622. Albertus was an Aristotelian philosopher, an astrologer, and a profound student of medicine and physics. During his youth, he was considered of deficient mentality, but his since service and devotion were rewarded by a vision in which the Virgin Mary appeared to him and bestowed upon him great philosophical and intellectual powers. Having become master of the magical sciences, Albertus began the construction of a curious automaton, which he invested with the powers of speech and thought. The Android, as it was called, was composed of metals and unknown substances chosen according to the stars and endued with spiritual qualities by magical formulæ and invocations, and the labor upon it consumed over thirty years. St. Thomas Aquinas, thinking the device to be a diabolical mechanism, destroyed it, thus frustrating the labor of a lifetime. In spite of this act, Albertus Magnus left to St. Thomas Aquinas his alchemical formulæ, including (according to legend) the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone.

On one occasion Albertus Magnus invited William II, Count of Holland and King of the Romans, to a garden party in midwinter. The ground was covered with snow, but Albertus, had prepare a sumptuous banquet in the open grounds of his monastery at Cologne. The guests were amazed at the imprudence of the philosopher, but as they sat down to eat Albertus, uttered a few words, the snow disappeared, the garden was filled with flowers and singing birds, and the air was warm with the breezes of summer. As soon as the feast was over, the snow returned, much to the amazement of the assembled nobles. (For details, see The Lives of Alchemystical Philosophers.)

p. 151

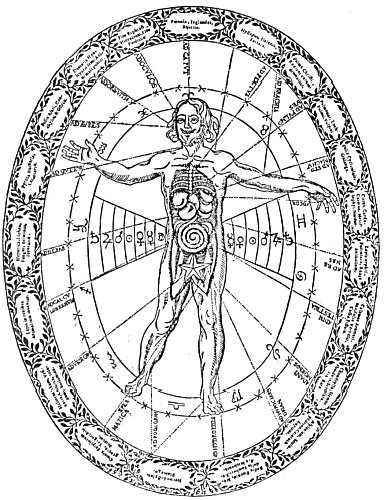

[paragraph continues] It was supposed that one early teacher of Paracelsus was a mysterious alchemist who called himself Solomon Trismosin. Concerning this person nothing is known save that after some years of wandering he secured the formula of transmutation and claimed to have made vast amounts of gold. A beautifully illuminated manuscript of this author, dated 1582 and called Splendor Solis, is in the British Museum. Trismosin claimed to have lived to the age of 150 as the result of his knowledge of alchemy. One very significant statement appears in his Alchemical Wanderings, which work is supposed to narrate his search for the Philosopher’s Scone: “Study what thou art, whereof thou art a part, what thou knowest of this art, this is really what thou art. All that is without thee also is within, thus wrote Trismosin.”

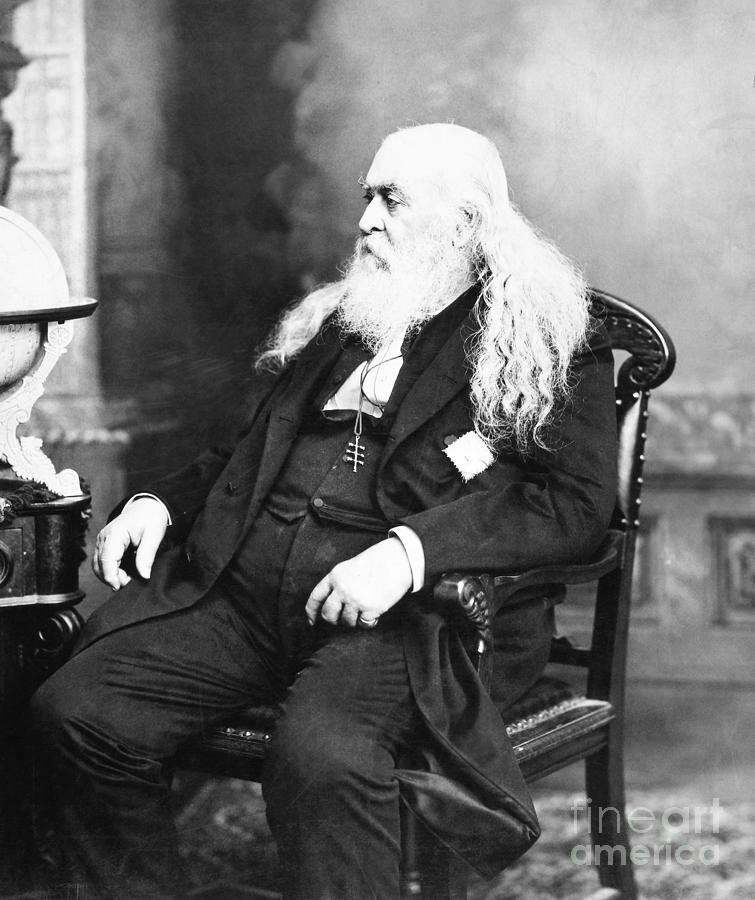

RAYMOND LULLY

This most famous of all the Spanish alchemists was born about the year 1235. His father was seneschal to James the First of Aragon, and young Raymond was brought up in the court surrounded by the temptations and profligacy abounding in such places. He was later appointed to the position which his father had occupied. A wealthy marriage ensured Raymond’s financial position, and he lived the life of a grandee.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.