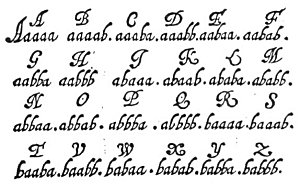

The next step is to run all the letters together; thus: baabaaabaaaabaaaaaabababaabbbabababaabaaaabaaaaaaa. All the combinations used in the Baconian biliteral cipher consist of groups containing five letters each. Therefore the solid line of letters must be broken into groups of five in the following manner: baaba aabaa aabaa aaaab ababa abbba babab aabaa aabaa aaaaa. Each of these groups of five letters now represents one letter of the cipher, and the actual letter can now be determined by comparing the groups with the alphabetical table, The Key to the Biliteral Cipher, from De Augmentis Scientiarum (q.v.): baaba = T, aabaa = E, aabaa = E; aaaab = B; ababa = L; abbba = P; babab = X; aabaa = E, aabaa = E; aaaaa = A; but the last five letters of the word riches being set off by a period from the initial r, the last five a‘s do not count in the cipher. The letters thus extracted are now brought together in order, resulting in TEEBLPXEE.

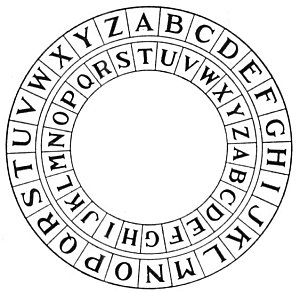

At this point the inquirer might reasonably expect the letters to make intelligible words; but he will very likely be disappointed, for, as in the case above, the letters thus extracted are themselves a cryptogram, doubly involved to discourage those who might have a casual acquaintance with the biliteral system. The next step is to apply the nine letters to what is commonly called a wheel (or disc) cipher (q.v.), which consists of two alphabets, one revolving around the other in such a manner that numerous transpositions of letters are possible. In the accompanying cut the A of the inner alphabet

AN EXAMPLE OF BILITERAL WRITING.

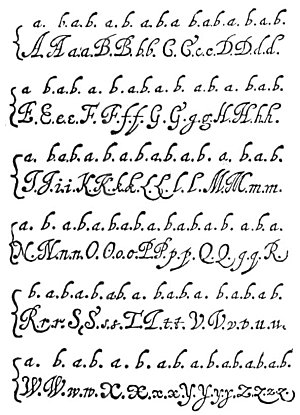

In the above sentence note carefully the formation of the letters. Compare each letter with the two types of letters in the biliteral alphabet table reproduced from Lord Bacon’s De Augmentis Scientiarum. A comparison of the “d” in “wisdom” with the “d” in “and” discloses a large loop at the top of the first, while the second shows practically no loop at all. Contrast the “i” in “wisdom” with the “i” in “understanding.” In the former, the lines are curved and in the latter angular. A similar analysis of the two “r’s” in “desired” reveals obvious differences. The “o” in “more” differs only from the “o” in “wisdom” in that it a tiny line continues from the top over towards the “r.” The “a” in “than” is thinner and more angular than the “a” in “are,” while the “r” in “riches” differs from that in “desired” in that the final upright stroke terminates in a ball instead of a sharp point. These minor differences disclose the presence of the two alphabets employed in writing the sentence.

THE KEY TO THE BILITERAL CIPHER.

From Bacon’s De Augmentis Scientiarum. After the document to be deciphered has been reduced to its “a” and “b” equivalents, it is then broken up into five-letter groups and the message read with the aid of the above table.

A MODERN WHEEL, OR DISC, CIPHER. The above diagram shows a wheel cipher. The smaller, or inner, alphabet moves around so that any one of its letters may be brought opposite any me of he letters on the larger, or outer, alphabet. In some, cases the inner alphabet is written backwards, but in the present example, both alphabets read the same way.

THE BILITERAL ALPHABET.

From Bacon’s De Augmentis Scientiarum. This Plate is reproduced from Bacon’s De Augmentis Scientiarum, and shows the two alphabets as designed by him for the purpose of his cipher. Each capital and small letter has two distinct forms which are designated “a” and “b”. The biliteral system did not in every instance make use of two alphabets in which the differences were as perceptible as in the example here given, but the two alphabets were always used; sometimes variations are so minute that it requires a powerful magnifying glass to distinguish the difference between the “a” and “b” types of letters.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.