When the Insinuator has found means of binding the Novice to the Order by such oaths, and especially when the young candidate shall have recognized without hesitation that strange and awful right which subjects the life of every citizen to the satellites of Illuminism, should any be unfortunate enough to displease its Superiors; when the Novice is blinded to such a degree as not to perceive that this pretended right, far from implying a society of sages, only denotes a band of ruffians and a federation of assassins like the emissaries of the Old Man of the Mountain; when, in short, he shall have submitted himself to this terrible power, the oath of the modern Seyde is sent to the archives of the Order. His dispositions then prove to be such as the superiors required to confer on him the second degree of the preparatory class; and the Insinuator concludes his mission by the introduction of his pupil.

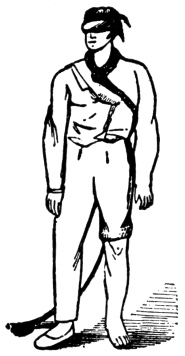

At the appointed time in the dead of the night, the Novice is led to a gloomy apartment, where two men are waiting for him, and, excepting his Insinuator, these are the first two of the Sect with whom the Novice is made acquainted. The Superior or his Delegate holds a lamp in his hand half covered with a shade; his attitude is severe and imperious; and a naked sword lies near him on the table. The other man, who serves as Secretary, is prepared to draw up the act of initiation. No mortal is introduced but the Novice and his Insinuator, nor can any one else be present. A question is first asked him, whether he still perseveres in the intention of entering the Order. On his answering in the affirmative, he is sent by himself into a room perfectly dark, there to meditate again on his resolution. Recalled from thence, he is questioned again and again on his firm determination blindly to obey all the laws of the Order. The Introducer answers for the dispositions of his pupil, and in return requests the protection of the Order for him.

“Your request is just,” replies the Superior to the Novice. “In the name of the most Serene Order from which I hold my powers, and in the name of

p. 437

all its Members, I promise you protection, justice, and help. Moreover, I protest to you once more, that you will find nothing among us hurtful to Religion, to Morals, or to the State;”—here the Initiator takes in his hand the naked sword which lay upon the table, and, pointing it at the heart of the Novice, continues, “but should you ever be a traitor or a perjurer, assure yourself that every Brother will be called upon to arm against you. Do not flatter yourself with the possibility of escaping, or of finding a place of security.—Wherever thou mayst be, the rage of the Brethren, shame and remorse shall follow thee, and prey upon thy very entrails.”—He lays down the sword.—”But if you persist in the design of being admitted into our Order, take this oath:”

The oath is conceived in the following teens:

“In presence of all powerful God, and of you Plenipotentiaries of the most high and most excellent Order into which I ask admittance, I acknowledge my natural weakness, and all the insufficiency of my strength. I confess that, notwithstanding all the privileges of rank, honours, titles, or riches which I may possess in civil society, I am but a man like other men; that I may lose them all by other mortals, as they have been acquired through them; that I am in absolute want of their approbation and of their esteem; and that I must do my utmost to deserve them both. I never will employ either the power or consequence that I may possess to the prejudice of the general welfare. I will, on the contrary, resist with all my might the enemies of human nature, and of civil society.” Let the reader observe these last words; let him remember them when reading of the mysteries of Illuminism; he will then be able to conceive how, by means of this oath, to maintain civil society, Weishaupt leads the adepts to the oath of eradicating even the last vestige of society. “I promise,” continues the adept, “ardently to seize every opportunity of serving humanity, of improving my mind and my will, of employing all my useful accomplishments for the general good, in as much as the welfare and the statutes of the society shall require it of me.

Moe is the founder of GnosticWarrior.com. He is a father, husband, author, martial arts black belt, and an expert in Gnosticism, the occult, and esotericism.